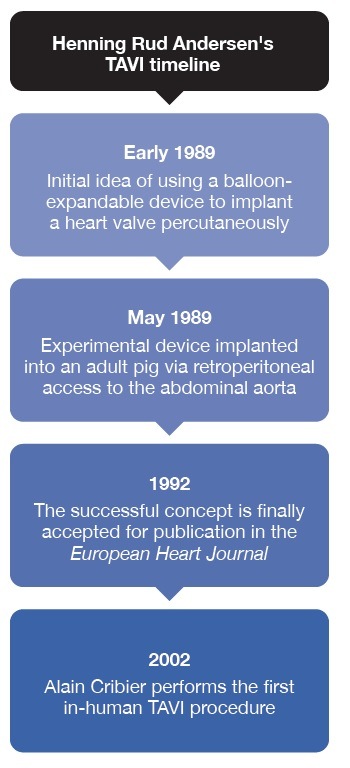

In the history of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), 16 April 2002 is a landmark date, with the implant of the first transcatheter aortic valve in a patient at the University Hospital of Rouen, Rouen, France, by Alain Cribier and his team. However, the story of TAVI goes back much further, driven largely by the ingenuity and tenacity of its creator, Henning Rud Andersen (Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark).

To mark the 20 years since the first implanted valve, Andersen, regarded by many as the ‘Father of TAVI’, speaks to Cardiovascular News about his development of the early transcatheter valve, the decades-long mission to bring the technology to fruition, where he sees TAVI going next and his advice for budding physician-inventors.

The story begins in 1989. Andersen was attending an interventional conference in Phoenix, USA, where he saw a talk by the developer of the balloon-expandable stent, Julio Palmaz, when he first chanced upon the idea of using a balloon-expandable device to implant a heart valve percutaneously. “It suddenly came out, just while I was sitting there, it took me one second to think ‘why not use the same technology, use the balloon and the stents and build a heart valve with a metal frame’,” recalls Andersen.

On return from his US trip, Andersen started work on what would become his prototype aortic valve, though he admits that, at the time, it was seen as being an outlandish concept. “When I went back to my professor and I told him that I have got this idea, he said to me that I was crazy. But he also told me to give it a shot,” he says. Colleagues too were less than optimistic about his prospects of bringing the idea to reality. As a result, Andersen set about without funding or industry support to work on the proof-of-concept valve.

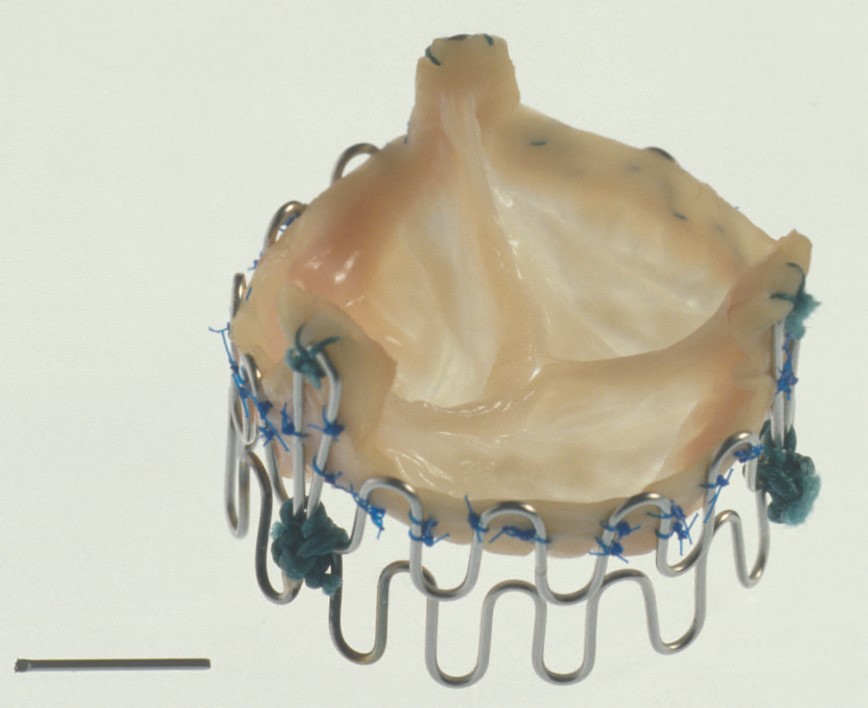

“What I built was a metal stent which had a valve inside. If you look at what is going out today, there is a metal stent, there is a foldable valve, and there is a balloon,” remarking that the concept is largely consistent with that of balloon-expandable valves that are still in use today. “When I am out presenting, I am still pointing at the engineers sitting there and saying ‘what the hell have you done within the last 30 years, nothing new has happened!’” he jokes.

“What I built was a metal stent which had a valve inside. If you look at what is going out today, there is a metal stent, there is a foldable valve, and there is a balloon,” remarking that the concept is largely consistent with that of balloon-expandable valves that are still in use today. “When I am out presenting, I am still pointing at the engineers sitting there and saying ‘what the hell have you done within the last 30 years, nothing new has happened!’” he jokes.

Initial experiments with the device involved implantations into adult pigs, which were performed via retroperitoneal access to the abdominal aorta. The first such implant was successfully performed on 1 May 1989, less than three months after his initial spark of the idea in Phoenix. After the first successful procedure, Andersen performed a series of implantations to attempt to refine the procedure.

“After five to ten animal implantations I was completely sure that this would be a revolution within interventional cardiology,” says Andersen. “Of course, I was turned down for many years, but my belief at that time was that this would be a technology that would develop and would be there for many years.”

Despite his own certainty, which had led him to invest in patents to protect his own financial interests and to secure funding to develop the idea, it was an uphill struggle to convince others that his successful concept could turn into the transformational procedure that it has become today. His initial attempts to publish the findings of his early studies were rebuffed by several well-known journals, before finally being accepted for publication in the European Heart Journal in 1992, now more than three years after the start of the story.

The initial publication was followed by the presentation of a poster at the 65th American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific meeting in New Orleans, USA in 1992, though Andersen admits that the idea did not gain huge traction at this time. Although he felt colleagues were slow to recognise the value of the concept, Andersen had secured some financial backing from Stanford Surgical Technologies (SST), based in California. Despite working with SST for a number of years in a bid to develop his research, Andersen said that his efforts had ground to a halt, and the company had instead opted to focus on the development of a technique for less invasive surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR).

Andersen says he began to see the idea gathering pace when it caught the attention of Stanton Rowe, a former director of development with Johnson & Johnson, and who had secured the licence for the coronary stent pioneered by Julio Palmaz, the initial spark for Andersen’s TAVI idea, on behalf of the company. When he saw the value in the idea, Rowe had formed Percutaneous Valve Technologies (PVT) in a bid to pursue the concept, with partners including Marty Leon and Alain Cribier. The company acquired the license agreement for the idea, which was later purchased by Edwards Lifesciences in 2004 for US$125 million.

Andersen recognised that it was the moment that PVT gained the licence to the idea that it took flight. “He [Stanton Rowe] established a budget of around US$20 million to start the development of my idea. I was in close contact with him, and they started to do all of the technical things down in Tel Aviv in Israel,” Andersen recalls.

Further animal experiments were conducted in Paris, led by Cribier and with the support of Leon who would travel in from the USA. Andersen’s own story then circles back to the beginning, when in 2002 Cribier performed the first in-human TAVI procedure. In fact, the circularity in Andersen’s story continues when his own father, aged 86 in 2011 underwent TAVI due to severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, and went on to live for a further nine years.

“My dad was nearly dying from his aortic stenosis. He was living outside the city, and he had a small farm, but he could not do anything anymore,” remembers Andersen. Though not involved in the procedure directly, which was performed by his colleagues in Aarhus, Andersen recognises the role that his innovation played in extending his father’s life.

“He lived until he was 95 and he had no symptoms from his heart for the rest of his life,” he says. “He had a very good life. Normally I would never say that I saved my dad’s life! I am very frequently asked about it, but I could never claim that I did!”

Andersen says he still follows the developments in the technology, and is proud of his contribution to the field. He says: “This was my baby, I created it, now it has grown up and it is a teenager. But it is a strong teenager and it will mature and mature.”

He believes that the expansion of TAVI, first in patients at extreme risk from surgery, and then latterly out into lower-risk populations, has been the right approach.” We started with the very fragile, very old patients who cardiac surgeons would not offer treatment to,” he comments. “It was the right place to start, because remember that this is a completely new, unproven procedure, maybe all the devices would have failed after six months. Nobody knew.”

To conclude the conversation, Andersen offers a quote from Albert Einstein about shifting paradigms. “If at first the idea is not absurd, then there is no hope for it.” This, he says, applies exactly to the development of TAVI.

Thanks 72 years w/ my TAVI in Morristown(NJ)–6 months ago

back at work 2 days later Can not thank you enough!!!!!