Discussion during the first day of the PCR Valves e-course (22–24 November, virtual) centred on the aortic valve and sought to answer key questions over the latest clinical evidence on transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in low-risk patients, as well as probing the decision-making process guiding the choice between transcatheter or surgical approaches to aortic stenosis.

Chaired by Antoinette Neylon (ICPS Massy, Massy, France) and Alexandra Lansky (Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, USA) the opening spotlight session of the three-day congress covered opportunities to refine TAVI safety and efficacy.

Michael Lee (Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong) offered insights on case selection, conduction disturbances and optimal medical treatment of patients post-TAVI, in the clinic and on the ward. During his presentation, Lee stressed the importance of a heart team approach to patient selection, involving cardiologists, interventionalists, surgeons, anesthesiologists and nurse coordinators, describing this multidisciplinary approach as ”critical” in the patient selection process.

He described the imaging modalities used within his centre for patient assessment, including echocardiogram and CT imaging, before elaborating on the selection criteria for patients undergoing TAVI.

He said: “You look at the aorta, annulus, as well as the peripheral arteries, and see if they are suitable for a TAVI procedure. We also look at the coronary arteries, both in terms of CT coronary angiogram or invasive coronary angiogram, and at the end of the day we come back to the heart team to decide whether the patient is suitable for TAVI or surgical AVR [aortic valve replacement].”

The team will determine whether the patient is having symptomatic severe aortic stenosis, Lee said, as well as assessing comorbidities, frailty and cognitive function—and considering the patient’s age and preference.

“With accumulating evidence we are moving from high-risk to intermediate [patients], and now we are embarking on the low-risk group of patients,” Lee commented. “At the end of the day, no matter what kind of patients we are treating, these criteria of patient selection, and then come back to a heart team approach is the cornerstone of our programme.”

Turning to conduction disturbances, Lee commented that this has “always been the Achilles” heel of the TAVI procedure”—occurring in up to “10% of all our TAVI patients”. He detailed a number of the criteria that may indicate that a patient is at high risk of requiring a pacemaker implantation post-TAVI, including the presence of pre-existing right bundle branch block or first degree heart block.

Lee then discussed the optimal antithrombotic treatment after TAVI, noting that current guidelines recommend at least three-to-six months of dual antiplatelet treatment (DAPT) after TAVI. However, he advocated a single-agent approach to antiplatelet therapy—as supported through the findings of the recently-published POPular TAVI trial.

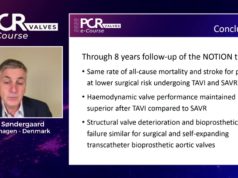

During the following spotlight session, speakers discussed the current evidence guiding the choice between TAVI and surgical aortic valve replacement in severe aortic stenosis. Cardiothoracic thoracic surgeon Michael Mack (Baylor Scott & White Health, Plano, USA) posed the question during his presentation: ‘what evidence is needed for TAVI to become the gold standard in aortic stenosis patients?’.

“In some ways I think you can say that TAVI already has become the gold standard,” Mack commented pointing to data published last week from the TVT registry in the USA, showing that the number of TAVI procedures carried out in 2019 had exceeded the number of overall aortic valve replacements for the first time.

However, Mack said that there are several evidence gaps that must be filled in order for TAVI to become more pervasive, including outcomes in patients under 65 years of age, long-term follow-up data on valve durability, outcomes in aortic regurgitation, treatment of concomitant coronary artery disease and bicuspid valve disease and further evidence on the role of anticoagulation. “In addition we do not know what the evidence is in the real-world compared to the trials,” he commented.

Mack noted that there are a number of trials being carried out to seek to fill this evidence gap—listing among them: EARLY TAVR, COMPLETE TAVR, REPEAT TAVR, WATCH TAVR and TAVR Unload—but cautioned that physicians should: “Mind the gap, before we further expand into TAVR while this evidence is generated.”

Following Mack, Stephan Windecker (Bern University Hospital, Bern, Switzerland) offered an outline of which patients are preferentially considered for surgical aortic valve procedures. “There remain a series of indications where surgery remains the gold standard and therapy of choice,” Windecker commented, listing patients with indication for mechanical prostheses, native valve aortic regurgitation, valvular disease associated with aortic root or ascending aorta aneurymsn, high-risk anatomies, concomitant severe coronary disease, and inability to perform transfemoral access and endocarditis among them.

Asked how he would prioritise three areas—high-risk anatomy, alternative access and coronary artery disease—in terms of priorities for study, he commented: “I would think that high-risk anatomies would be exceedingly difficult to study because of the heterogeneity, and the individual decision-making that is necessary. Equally, if it comes to alternative access there is not a single best option; you will have a patient where you may be able to a subclavian or an axillary approach, in the next patient you prefer transcaval access, in others transcarotid, and I think they are too heterogeneous to be bulked together. From the three options I think an important one remains aortic stenosis and concomitant coronary artery disease.”