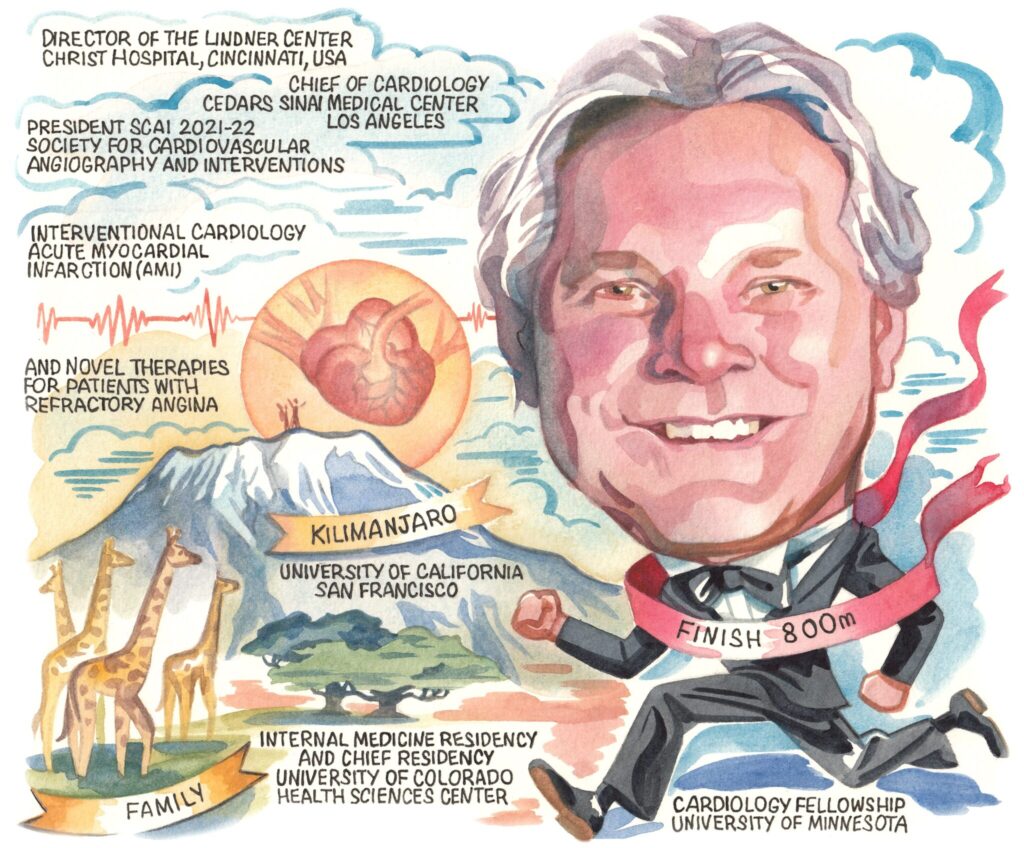

A pioneer of one of the first regional ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) systems in the USA, Timothy D Henry boasts an illustrious career, which most recently has seen him lead the interventional cardiology field on COVID-19 research, and serve as president of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI). He discusses how the field has developed during his 30 years in practice.

A pioneer of one of the first regional ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) systems in the USA, Timothy D Henry boasts an illustrious career, which most recently has seen him lead the interventional cardiology field on COVID-19 research, and serve as president of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI). He discusses how the field has developed during his 30 years in practice.

Why did you become a doctor?

I grew up in rural North Dakota. When I was in high school, my grandfather Howard Henry—who had run for state governor—died from a myocardial infarction (MI). That stimulated my interest in medicine, as nobody in my family had ever been a doctor.

When I was graduating from medical school, interventional cardiology did not really exist. I knew that I wanted to do internal medicine, rather than surgery, and it was clear at that time that cardiology was changing dramatically. You could do interventions that made people’s lives better, and almost everything we did was for the first time—you really had the opportunity to blaze a trail, which was great.

Who were your biggest influences?

This is a hard question because there are a lot of people to mention. Robert Wilson is an interventional cardiologist who was among the first to do coronary flow reserve. When I did my fellowship at the University of Minnesota, Bob was very involved in clinical research, and he developed the Doppler flow catheter, for example.

In my first job at Hennepin County Medical Center, I worked with Bob van Tassel who was the founder of the Minneapolis Heart Institute and was involved in the first angioplasty in the state of Minnesota. Later, I had the opportunity to work with Bob as the director of research at the Institute. One of the important things that Bob taught me was that when it comes to making plans, you cannot think big enough.

The TIMI Study Group have also been really important to me. It was through working with them that I learned how to do clinical trials, alongside the likes of Eugene Braunwald and Mike Gibson.

My father too was a big influence. He was an outstanding athlete and innovator, having trained as an architect, but then later working as a farmer. He taught me to be positive and innovative.

What has been the most important development during your career?

The most important development to me personally, and something I have been directly involved in, has been primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The development of regional STEMI systems—or even regional systems for care of all acute cardiovascular emergencies—have also been important.

Despite not being a structural heart specialist myself, you cannot talk about anything in interventional cardiology without mentioning transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). Looking back to the PARTNER Trial, which included people who had been turned down for surgery, TAVI has cut mortality among those patients in half.

Obviously, angioplasty itself has made a clearcut difference in people’s lives, but there have been so many innovations. When I look back at my career it is remarkable to think about how far things have come.

What has been the biggest disappointment?

One of the main things I do is to take care of patients with refractory angina, those who are not amenable to further revascularisation—including both advanced coronary artery disease and microvascular angina. I would say something that has not got across the goal line has been stem cell therapy. There has perhaps been too much hype, and this happens when we get away from treating it like medicine. I think some people saw it as a magic bullet that cures everything, which it was never going to be. When you look critically at some of the data, there have been some positive signals from double blind, placebo-controlled trials.

What are your research priorities?

Refractory angina and microvascular dysfunction are important areas of interest of mine right now. Those patients are still out there, and I probably do more microvasculature function tests than anyone else in the world! Microvasculature is the big unmet need. This includes young people who have angina, including more women than men. These could be post-PCI or post-chronic total occlusion (CTO) patients who still have chest pain. Heart attack patients who do the worst are those who have microvascular obstruction, and 75% of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) patients have abnormal coronary flow reserve—the point being that microvasculature is involved with everything. I think that in the next 10 years there is going to be a big focus on how we improve the microvasculature.

In Minneapolis, you developed the Level I heart attack network.

How has this changed STEMI care?

When you start anywhere new, you have to recognise the strengths and weaknesses, and look at the unmet needs to fix them. The best example I have is from when I went to the Minneapolis Heart Institute—a big hospital that does outreach among some 30 hospitals. It was perfectly designed to do the first STEMI system, which we called the Level I MI system. I could not have done that anywhere else.

We knew it was the right thing to do. People look at mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), but the impact of primary PCI is even far beyond that. It is not just the procedure but having a standardised protocol before and after so that you get comprehensive STEMI care in a guideline-based way. The outcome was shocking to me, we cut MI mortality in the state of Minnesota by 50% within two years.

You were at the forefront of research on COVID-19 through the North American COVID-19 STEMI (NACMI) registry. What is the impact of the pandemic on STEMI care?

Three years ago, I would never have foreseen myself specialising in COVID-19, but now I have over 30 papers on the subject published. In March 2020 we recognised many reports on social media that COVID-19 patients were coming to hospitals and were having MIs, but they appeared to have normal coronary arteries. The second thing that we noticed was that STEMI volumes were down, and we were wondering where they had all gone.

We have a STEMI registry called the Midwest STEMI consortium, made up of four large centres. Right now, that consists of more than 20,000 STEMI activations and it is a goldmine of information. I called all those sites and asked if they had seen their volumes drop, and they all had. I then called five other hospitals around the country, and we got their data from 2018 and 2019. We submitted a paper to the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC) on 3 April and it was published on 5 April, and it showed a 40% reduction in STEMI activations. What we had seen on social media was true.

We put the NACMI registry together within two weeks, through a partnership between SCAI, the American College of Cardiology, and the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology. We had 70 sites, and we now have more than 800 COVID-19-positive patients with STEMI in our database. We had the idea in March of 2020 and we were up and running by April 2020, with late-breaking data shared at TCT and published in October 2020. I think that has really impacted our treatment of COVID-19-positive patients. It has shown that it is safe to go to the cath lab, and that you still need to do primary PCI. COVID-19 is very bad, but our public health response was to scare people, and that meant that they did not come to the hospital, which was also bad.

What were you proudest to achieve as president of SCAI?

Being president of SCAI was one of the most satisfying years of my life. It has been really fantastic. During that time we started JSCAI—The Journal of the Soceity for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions—and started a Scientific Oversight Committee, pushing SCAI to be more scholarly and to increase research output from registries, surveys, and clinical trials. NACMI is a great example of how important SCAI is.

What is your most memorable case?

What is your most memorable case?

On my very last weekend on call in Minneapolis, I was involved in 21 cases, all involving STEMI, or out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). Case number 21 was at 2am on the Monday morning. It was a STEMI from a town around 100 miles away. The patient had been working in a factory and had a tearing in her chest. She came by helicopter—a part of our Level I programme—arrested twice on the way, was in cardiogenic shock and had a spontaneous coronary dissection on her left main. Despite being two hours away from a PCI centre, within 10 minutes of her reaching us we had a wire into the true lumen, and had stented the left main. It was a nasty left main dissection, God’s final exam! It is now eight years later and she has written a book and her ejection fraction (EF) is 60%. I think in most places in the world she may have died, especially being so far away from a PCI centre and if we had not had the Level I system.

Outside of medicine, what are your hobbies and interests?

I was involved in athletics in high school and college, and I still enjoy all sports—both watching and participating—I run, I play golf, I cycle, I hike. I have climbed Mount Kilimanjaro with my son. I also like music and the theatre, and I love to travel. My family are really important—I have three great kids and my family are a key part of my life.

FACT FILE

Current and past appointments

- Lindner Family Distinguished Chair in Clinical Research,

The Christ Hospital - Medical Director, The Carl and Edith Lindner Center for Research, The Christ Hospital

- Chief of Cardiology, Cedars Sinai Medical Center

- SCAI President

- JSCAI Editorial Board

Research interests

- Interventional cardiology

- Acute myocardial infarction

- Refractory angina

Education

- University of California at San Francisco, professional education

- University of Colorado, internal medicine residency

- University of Minnesota Medical Center, interventional cardiology fellowship programme

Awards and accolades

- Best Doctors in America 2007‒2017

- American Heart Association Heart and Stroke Hero Award in Research 2013

- LUMEN Global Lifetime Achievement Award in MI 2012

- Master Fellow, SCAI