The rapid growth of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has been the story of the last two decades in the treatment of aortic valve disease. Favourable results from major trials covering a broad population of patients have widened access to a minimally invasive treatment option which has now overtaken surgery as the predominant treatment strategy for many aortic stenosis patients, for whom previously only surgery may have been considered.

The rapid growth of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has been the story of the last two decades in the treatment of aortic valve disease. Favourable results from major trials covering a broad population of patients have widened access to a minimally invasive treatment option which has now overtaken surgery as the predominant treatment strategy for many aortic stenosis patients, for whom previously only surgery may have been considered.

“While I remain an ardent supporter of TAVI and its role in the management of aortic valve disease, there are times when surgery may be more appropriate for anatomic or durability reasons. We live in an environment that is consumer based, and despite the recent literature—from which there are signals that all-TAVI all the time may not be ideal—patients, consumers and providers are seeking alternatives to an anterior chest approach surgical option,” cardiac surgeon Vinay Badhwar (West Virginia University [WVU], Morgantown, USA) tells Cardiovascular News, discussing the treatment of aortic stenosis within his institution.

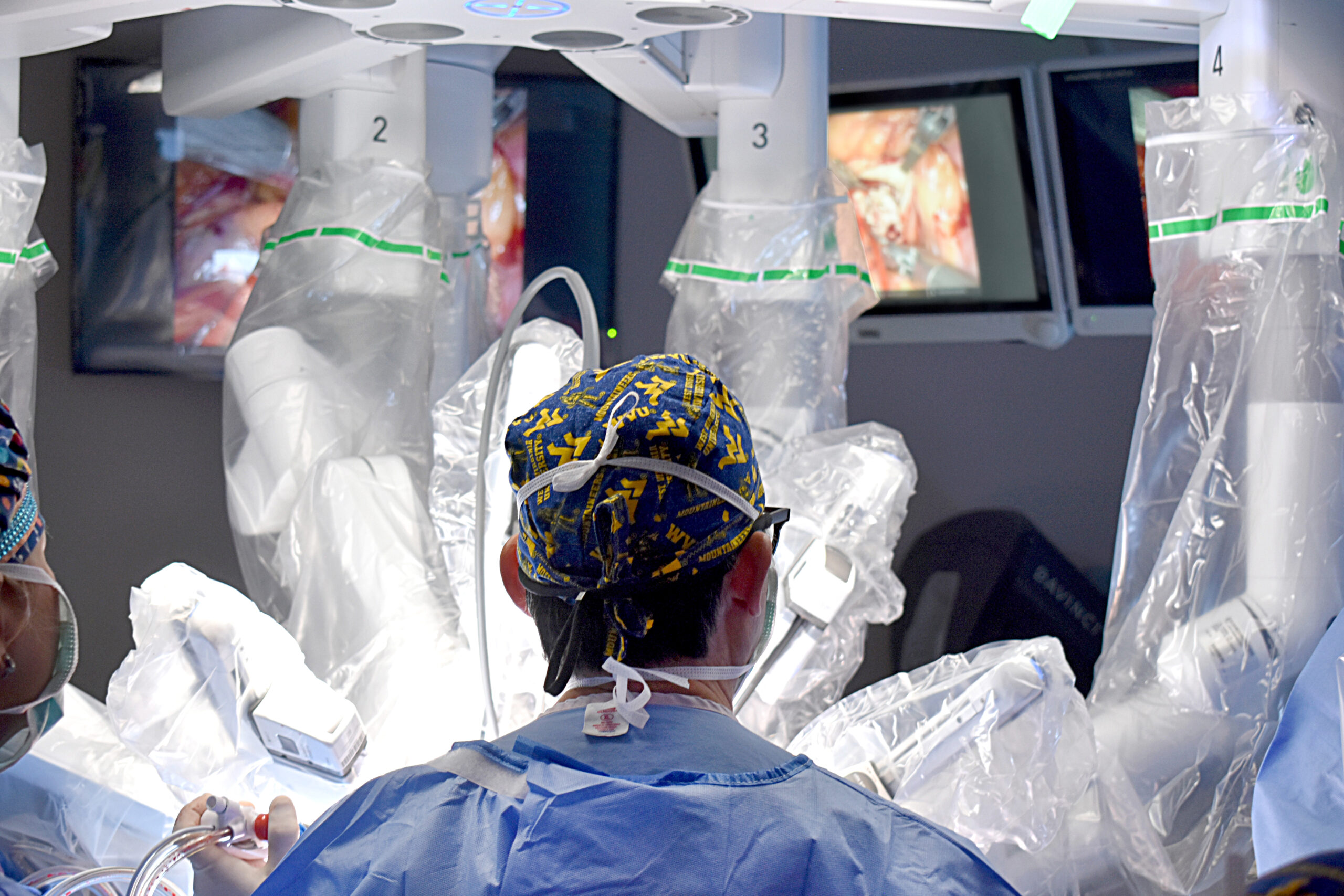

WVU was the first in the world to develop robotic aortic valve replacement (RAVR) with access via a 3cm transaxillary right lateral mini thoracotomy, and then routinely use this alongside traditional surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) and TAVI to treat symptomatic aortic stenosis. The procedure ultimately sits at a middle ground between the two established interventional strategies, potentially offering the longer-term durability typically expected with a SAVR procedure, albeit achieved without the need for fully invasive surgery.

The robotic platform for the RAVR procedure is performed via a similar approach used for robotic mitral valve surgery, a well-established technique performed in many centres worldwide. RAVR uses traditional biologic or mechanical valves rather than a sutureless prosthesis and, in addition, allows for concomitant mitral or tricuspid valve procedures, as well as arrhythmia therapies such as the maze procedure or left atrial appendage closure.

After honing the technique through cadaver experiments, Badhwar and the WVU team performed the first-in-human RAVR case in January 2020 and are now well into the hundreds of cases. Many centres around the world have adopted the WVU RAVR platform and integrated this as a heart team option. Initial results have been promising. At the recent European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) 2024 annual meeting (9–12 October, Lisbon, Portugal) Badhwar presented longitudinal outcomes from the first 300 consecutive patients undergoing RAVR across 10 established robotic cardiac surgery programmes at centres in the USA, Europe, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, Taiwan and Australia, reporting low rates of operative mortality (0.7%), stroke (1%), and pacemaker implantation (2.3%), following the procedure.

These early results have prompted optimism that RAVR could emerge as a viable alternative to TAVI, and indeed at WVU, Badhwar says that the development of RAVR has created a new pathway for care. “Our team philosophy is to always do the right thing for the right patient at the right time,” he comments, noting that the choice of therapy goes beyond simply determining which procedure is most appropriate based upon the age of the patient. “Our programme looks at the anatomy, the patient comorbidities and condition, as well as age, to determine treatment. Our heart teams, which are led by our cardiologists, have followed the short-term and long-term results of RAVR as compared to TAVI. Instead of many centres approaching patients with aortic stenosis with a TAVI first strategy—here it is RAVR first. Our cardiologists have flipped that management philosophy.”

The WVU team continues to explore the potential avenues for the robotic approach, and in October 2024 completed a pioneering procedure combining RAVR with a coronary artery bypass—a world first—which they say may extend robotic surgery options to many more patients.

Alongside developing the procedure, Badhwar and his colleagues have worked on training pathways that have helped to seed the technique in other centres across the USA and globally, with around 20 sites now proficient in the approach, with many more in development. “Our goal was to transparently develop this in such a way to make it reproducible and standardisable,” he says. “One of the challenges with the implementation of any new technology or technique is that while it’s great to do one or two cases, in order to make it sustainable and reproducible in multiple centres with a minimal learning curve, one must make it somewhat standardised.”

As well as disseminating guidance and best practice on how to learn the robotic aortic procedure, WVU recently hosted a two-day international RAVR symposium (14–15 November, Morgantown, USA) to bring together innovators and practitioners to look at the challenges and opportunities in growing this approach further.

“When some see these new things via edited videos or brief presentations, they think it is impossible, or it is going to take all day. This is not the case. These are operations that can be done in only a few hours, efficiently and, most importantly, very safely. That was one of the most important things we wanted to share,” says Badhwar reflecting on the take-home messages from the event. “We consistently receive feedback from other surgeons and cardiologists around the world as to where RAVR now fits in their armamentarium, so I think we are entering a potentially exciting next chapter for both cardiologists and surgeons where a healthy equipoise of therapy exists within multidisciplinary heart teams.”

What of the future for the technique, and its prospects for becoming a widely used alternative to TAVI and SAVR? Badhwar says it is reasonable to expect that centres that are already established in performing robotic mitral surgery procedures can learn the RAVR technique, with experience from his own centre pointing to a learning curve of between five and 10 cases. However, he is cautious about predicting an explosion in sites adopting this technique.

“The excitement is significant, but it must be realistic and tempered. We have to do this in a diligent and transparent way, keeping quality always first. It is technically a little bit more demanding than robotic mitral surgery, largely because we are dealing with the aorta. However, once the learning curve is crested, particularly in experienced robotic teams, then it becomes more and more routine just like any other robotic operation.”