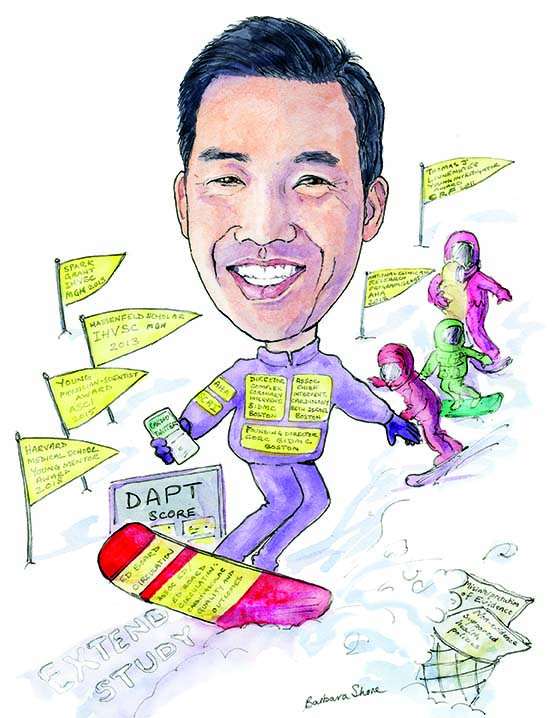

Robert W Yeh (Department of Medicine, Richard A. and Susan F. Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA) believes that it is a “humbling privilege” that patients put so much trust in the judgement and ability of physicians. He talks to Cardiovascular News about his diverse range of interests in interventional cardiology from complex coronary interventions to health services research, which includes his work on developing the dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) Score, the PARACHUTE Trial, and evaluating national health policies.

Why did you decide to become a doctor and why, in particular, did you decide to go into interventional cardiology?

The idea of being able to help people at the time of their greatest need was initially what attracted me to the medical profession, and specifically to interventional cardiology. There is certainly a profound sense of satisfaction in being able to reverse the course of a potentially fatal presentation, such as ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or to provide someone with relief from debilitating angina. On top of that, so much of what we do as physicians involves serving as faithful agents, advisors and counsellors for our patients and their families. There are not too many professions in which you get to spend your day doing everything you can to help someone through something difficult physically and emotionally. Patients place so much trust in our judgment and ability. It is a humbling privilege.

Who have been your career mentors?

There have been so many. IK Jang (Cardiology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA) was really the first person to pique my interest in cardiology research, and I chose to combine research and interventional cardiology in large part because of his mentorship. Laura Mauri (Vice President, Global Clinical Research & Analytics, Medtronic) has been an incredible role model in her leadership of clinical trials. I look to Rob Gerszten and Peter Zimetbaum (both Harvard Medical School; Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, USA) as sounding boards and confidants almost every day.

What has been the most important development in interventional cardiology during your career?

The field is so dynamic and it is hard to pick just one! Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) came to market at the time of my fellowship and has been so disruptive, and the field of chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), which is what I spend much of my clinical time doing, has also advanced tremendously. But I am going to go out on a limb and say that interventional cardiology engagement on social media will have a growing and substantive impact on providing educational content to rank and file interventionalists, increase engagement of a much broader group into evidence development, expose the field to more public scrutiny and accountability (often a good thing), and create patient-centred norms for our practice.

What has been the biggest disappointment?

I have two. The first disappointment has to do with the consistent misinterpretation of evidence that happens in our field, often used to justify our pre-existing beliefs. This happens on “both sides” of most debates, and it is often exacerbated by media eager for a sound bite. There is so much low quality evidence that is being produced that we can all find a study that seems to support our practice if we look hard enough. We should have higher standards than that.

The second, related area is the growing body of non-evidence supported health policies that surround cardiovascular care—policies (in the USA at least) such as public reporting of PCI mortality statistics and 30-day readmission metrics and penalties. I have spent a fair amount of time studying the potential unintended consequences of policies such as these, and they occur frequently. Moving forward, we ought to hold health policies to the same standard that we hold new medications or devices—both cost the healthcare system money and have potential adverse consequences that can hurt patients.

Of the research you have been involved in, what do you think has had (or will have) the greatest impact on clinical practice?

Thus far, the creation of the DAPT Score has probably had the most impact on clinical practice of the projects I have been involved with. I have had a lot of feedback from cardiologists around the world letting me know that they have found it very useful in clinical care. The PARACHUTE trial, a satirical study in the BMJ, has been by far our most popular study, and probably will be the most cited paper I ever work on—but I hope does NOT change skydiving practices! Finally, we’ve recently published a paper in JAMA about readmissions policies in the US that could potentially impact the manner in which future policies are created and evaluated – we are in the midst of discussing the implications of our findings with policymakers in Washington currently.

Several of the studies you have been involved in have focused on DAPT, including the development of the DAPT Score. What is your approach to ensuring a patient receives optimum DAPT?

I think the first thing to appreciate is that there is no “free lunch”. Longer duration of DAPT means more bleeding problems, but it also means fewer ischaemic events. There has been this movement to shorten DAPT duration to fewer and fewer months, which I think is a mistake for many patients. I try to practise what I preach, which means estimating the DAPT Score in my head for all patients getting PCI, and combining that with clinical judgment and patient preference to determine what might be a good DAPT regimen for any individual patient.

What are your current research interests?

I am currently leading the NIH-sponsored EXTEND Study to merge several clinical trials with a diverse set of clinical and administrative claims databases to help validate the use of alternative sources of passively collected data to support clinical trials. There has been much discussion of designing more efficient ways to collect data on patients in clinical trials, but much less validation work to ensure that such an approach is both feasible and accurate. We hope this work can lend insight into newer ways of assessing therapeutic efficacy in trials.

We also have a growing body of work evaluating national health policies and their consequences. It is surprising how little work there is evaluating health policies that is actually led by physicians on the ground floor who are taking care of patients most affected by these policies. We try to bring an everyday cardiologist’s perspective to much of the health policy evaluation we do, which I think has been missing.

You are an active member of #CardioTwitter. What are the advantages and disadvantages of using social media to discuss interventional cardiology?

You are an active member of #CardioTwitter. What are the advantages and disadvantages of using social media to discuss interventional cardiology?

There is a lot to bite off here, and I have written an article in Circ Outcomes describing in more detail what I think are the real strengths and weaknesses of cardiologist engagement in social media (Yeh RW. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2018. Epub). In a nutshell, the ability to give nearly an equal voice to all participants, to engage with experts from around the world directly, to consume and disseminate new information in near real time—these are powerful attributes of social media and in particular Twitter. Of course, conversations can degenerate into virtual shouting and name calling and there tends to be perhaps less civility on Twitter than you might see at a scientific meeting. Sometimes inaccuracies get propagated quickly. I think the advantages greatly outweigh the disadvantages though.

What was your most memorable case?

I do not want to give too many details, so as not to identify the patient, but there was a young woman who had terrible multivessel spontaneous coronary dissections. She was actually undergoing a catheterisation in a room next to the one I was working in when an emergency code was called because her vessels were shutting down and she was beginning to arrest. My colleague asked for help, and thankfully, we were able to use some techniques we often use in chronic total occlusion PCI to restore flow, and stabilise her. She ended up doing well. Her young family was terrified, sitting together in the waiting room—there were many tears and emotional embraces shared nearly daily as she slowly recovered. It was an experience that really showed me the importance of merging technical competence, clinical judgment and compassion. It was a really powerful experience.

What advice did you receive at the start of your career that you now pass on to those who you mentor?

David Torchiana (the now CEO of Partners Healthcare) told me many years ago about this simple framework he learned to think about his daily work. Everything can be placed on two axes. The first is the axis of importance, and the second is the axis of urgency. Things that are urgent and important —like a family health emergency—obviously those things need to rise to the very top of our priorities. Things that are non-urgent and unimportant—we might as well push those things down the list. But our ability to prioritise accomplishing things that are important, but not necessarily urgent over things that are not important, but urgent—that ability is constantly being challenged, but crucial for success and happiness. It is a great lesson that we constantly need to remind ourselves.

Outside of medicine, what are your hobbies and interests?

Family time is my priority outside of the hospital. My wife and I have three wonderful children and we love spending time together, and with our extended group of friends we call our Boston Family—old friends from college, medical school and training. My wife and I and our two older kids all really love snowboarding together. We are waiting for the little one to learn how to walk first before indoctrinating him into our favourite winter pastime.

Current appointments

- 2017–present: Associate chief, Interventional Cardiology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, USA

- 2017–present: Director of Complex Coronary Intervention, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, USA

- 2015–present: Director, Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, USA. Centre is devoted to outcomes research in three primary areas—health policy evaluation, comparative effectiveness research, and use of novel sources of data for risk prediction

Training

- July 2009–June 2010: Fellow, Interventional Cardiology Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA

- July 2006–June 2009: Cardiovascular Disease University of California, San Francisco, USA

- July 2004–June 2006: Internal Medicine Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA

- 1999: Masters in Business Administration (with Distinction), University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

- 1998: Masters in Health Policy, London School of Economics/Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London

Society memberships

- 2014–present: Fellow of the American Heart Association, on Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research and on Council on Epidemiology and Prevention

- 2012–2015: Fellow, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions

- 2011–present: Fellow of the American College of Cardiology

Editorial posts

- 2013–present: Associate editor, editorial board, Circulation: Cardiovascular

Quality and Outcomes

Awards

- 2018: Harvard Medical School Young Mentor Award

- 2015: Young Physician-Scientist Award American Society for Clinical Investigation (ASCI)

Publication

- Yeh R et al. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma when jumping from aircraft: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2018. Epub.