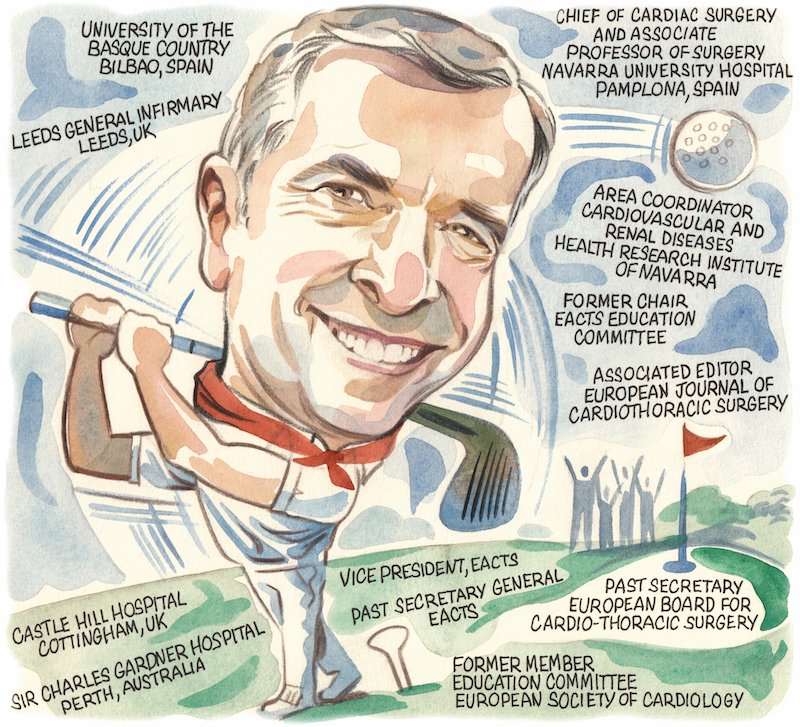

Hailing from Pamplona, northern Spain, cardiac surgeon Rafael Sádaba was born and raised in a medical family. Following an education that took him across the world to Australia via East Yorkshire, Sádaba has returned to his native Spain where he is now professor of cardiac surgery at Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra. An active and prominent member of the cardiac surgery community, Sádaba tells Cardiovascular News about the importance of cross-border collaboration and where he sees the specialism heading in the future.

Hailing from Pamplona, northern Spain, cardiac surgeon Rafael Sádaba was born and raised in a medical family. Following an education that took him across the world to Australia via East Yorkshire, Sádaba has returned to his native Spain where he is now professor of cardiac surgery at Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra. An active and prominent member of the cardiac surgery community, Sádaba tells Cardiovascular News about the importance of cross-border collaboration and where he sees the specialism heading in the future.

How did you arrive at a career in medicine, and then why did you gravitate to cardiac surgery?

When I was born in 1967 my father was working as a cardiologist at a lung hospital in northern Spain. Cardiac surgery was in its very beginnings there, with thoracic surgeons already starting to do some of these procedures. My father was a junior doctor at the time, and although he was a cardiologist, he was very much involved in the few cardiac surgery cases that were being done at the time.

One of my very early memories is of my mother telling me that my father was performing an “extracorporeal” operation that day, an operation with a heart-lung machine. Though I didn’t know what it meant, I knew that he wouldn’t be home until very late into the evening. I spent my very first few years in that hospital as my parents had been living in hospital accommodation, so you could say that I was born into it.

You may ask why I didn’t follow my father’s footsteps into cardiology, but I always joke that sons should go further than their fathers! I like being more effective than prescribing drugs, that was what made me go into medicine and cardiac surgery.

As one of three brothers, my father was very supportive of us, and all three of us are doctors. One is an interventional cardiologist, one a radiologist, and myself a cardiac surgeon. Of all the subjects in medical school, the cardiovascular physiology and system was the one I always found the most interesting, dedicated more time to, and eventually that made me go into cardiac surgery.

Who have been the biggest influences on your career?

I went to medical school in Bilbao in the Basque country, but I always wanted to go elsewhere to see the world—I didn’t care where, I just wanted to move. That took me to the UK, where I ended up in various different positions. I have a strong tie to Yorkshire, in northern England, having done my basic surgical training in Hull and then going on to do higher training in cardiothoracic surgery in Leeds. My eldest son was born in Beverley and my other two children, a son and a daughter, were both born in Leeds.

After that I had a big opportunity to spend a year in Perth, Australia, to undertake cardiac surgery training.

Do I have a particular mentor? No. The surgeons with whom I worked in Leeds, Joe McGoldrick, Philip Kay and Chris Munsch, to name a few, were like my parents and I have great memories of all of them, as well as Mark Newman in Perth.

My experiences overseas have been crucial to my surgical career. I not only thoroughly enjoyed collaborating with diverse individuals and adapting to various work environments, but I also gained a broader perspective that allows me to respect and appreciate different methods for addressing similar challenges.

For me it was very enriching to go to these different places. Any doctor, whether they specialise in cardiac surgery, cardiology or any other specialty, should take the opportunity to go to new places to learn. You gain something just from being there and seeing how things are done differently. Not wrong, better or worse, but differently. You learn things from what you see, from ways of doing things that are different, and you learn a lot from the people you meet. That personal touch, knowing different personalities and how they face the same problem in different ways.

Perhaps the biggest influence, however, was that of my father. He basically taught me the craft of medicine, how to be a good doctor.

During your career what has been the biggest change in cardiac surgery?

Being able to offer less invasive treatment for patients has been a change in mentality. In the beginning, it was big surgeries with big wounds, but now there has been a shift to less invasive procedures. Why I think this is important goes back to what is valuable to a patient. If you operate on somebody and you tell them that they cannot go back home for another six or seven days, or back to work for another two or three months, that can be very difficult.

Being able to offer less invasive treatment for patients has been a change in mentality. In the beginning, it was big surgeries with big wounds, but now there has been a shift to less invasive procedures. Why I think this is important goes back to what is valuable to a patient. If you operate on somebody and you tell them that they cannot go back home for another six or seven days, or back to work for another two or three months, that can be very difficult.

Minimally invasive surgery means we can get people back to their normal activities, quicker, with similar long-term results. That has been the important shift in mentality and what makes interventional cardiology very competitive. I have grown up in the age of maximally invasive surgery, so I don’t consider myself an expert in minimally invasive procedures, but I make sure that is how my team sees the future and what we are preparing to move towards.

What has been your main area of focus for research?

As a specialty, cardiac surgery has not been very research oriented and most of the research we do is based on retrospective analysis of patients. That is one of the things we need to improve upon and develop further, and something I have a special interest in. At my institution we have a basic science lab which concentrates on translational research in cardiology and my interest has been at the level of basic science in heart valve disease mainly on aortic stenosis, but also in other types of aortic and mitral valve disease.

It also helps to escape the stress of everyday surgery and complex cases and is something that I enjoy. Cardiac surgery is quite intense and the part of your day that is spent in the operating theatre and looking after patients is so time and attention consuming. It is so important to keep yourself up to date with new developments that are coming out. Techniques have developed so much that we now have sub-specialisation, so there is little time for surgeons to dedicate time to go to the lab and do basic science research. There also isn’t much profit in return for the time you invest in it.

In the past, cardiac surgeons were always at the forefront of science and developments, whereas now we don’t have such an innovative mentality, and this is a problem for us. We have to think outside of the knife, needle and stitches, and look into important aspects of our daily activities.

Are cardiac surgery and interventional cardiology competing or complementary specialties?

My view is that they should be complementary, but the fact is that they are competing, and both sides have responsibility. Surgeons see interventional cardiology as competition because they feel that they are taking patients away. From the other side, interventional cardiologists want to get more and more patients, and they want to do more things that they weren’t doing before, so there is competition. Sometimes interventional cardiologists may want to go a bit too far too fast, but we will all be able to go much further if we work in a way that is complementary to each other.

In my environment, I am very lucky in that we have that view. Both sides are going to do far more if we help each other fully and truly. Once both sides understand that, life is so much easier.

What is your advice to young cardiac surgeons who are just starting out in the field?

My view is that the specialty is at a crossroads and in danger of lagging behind other alternative treatments if we don’t wake up and move forward. We must concentrate on adding value to the care we give to our patients, making sure that we put them, their interests and preferences, before anything else. Processes must be streamlined to offer safe procedures, early recovery, and long-lasting results free from complications. Demands on surgical abilities will increase, as surgical procedures become more complex and the population ages.

How has your involvement in the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) contributed to your professional life?

One of the things I have found most interesting from being a part of EACTS is that you are always in contact with first-line research and scientific development. It is a scientific society which means that, not only do you have access to the research and science, but to the people who lead that research, and for me that is what has helped me the most. These scientific organisations give you the opportunity to attend courses and other educational activities that show you what you need to know and the skills you have to develop.

A big part is networking. It is an overused word, but it is true. You may get to know people who you admire, who are leaders in the field, and learn from these people. You learn a lot from top surgeons, but also from peers who you may be able to talk more openly with.

EACTS is evolving, and I think this is what distinguishes us from our American colleagues, for instance, who acknowledge this when they come to our annual meeting. I have been a part of the programme committee for many years, and there is a willingness to constantly evolve and do better each year. We have to try new things and recognise that members and non-members attending the meeting want to feel a part of it. They want to see that there is more interaction and that they can play a bigger role, instead of just seeing the usual suspects who are always on the stage. That is why, in most of our presentations, we have six or seven minutes for the presentation and another six or seven minutes of discussion to give attendees an opportunity to speak.

Having more hands-on opportunities in the meetings, giving surgeons more opportunities to come and try things, giving industry the opportunity to showcase their devices and giving them the opportunity to interact with surgeons, are also important.

We are the best attended meeting in the world for cardiac and thoracic surgery and I think that is a reflection of the quality that we offer. We are a European association but we try to open up globally and attract people from all parts of the world. We have interest from Latin America and we are working more in Africa to try to help surgeons and their patients in those parts of the world.

What does your life outside of medicine look like?

I try to play golf as much as I can. I try to go out to walk or run every day, even if it is just for a short time. I also like seeing different parts of the world, travelling and meeting new people—although outside of cardiac surgery I don’t have many opportunities. Now that my children have grown up, I grasp every opportunity to have the five of us together.