Wanting to be like his father, Philip Urban (Cardiovascular Department, Hôpital de la Tour, Geneva, Switzerland) initially considered a career in banking. However, after finding business school “too dry”, he switched to medicine. He talks to Cardiovascular News about his career mentors, how the stent represented a major advance in interventional cardiology, and discusses his work with the Center for European Research in Cardiovascular Medicine (CERC).

Why did you decide to become a doctor and why, in particular, did you choose to specialise in interventional cardiology?

In the early 70s, after secondary school, I first studied at a business school; however, after a few months, I found that the curriculum was too “dry” for my tastes. Therefore, I switched to medicine and I have never looked back!

As a medical student, I had the opportunity to spend some time at the Hammersmith Hospital in London, where I followed some great figures of those times—such as John Goodwin, Celia Oakley and Attilio Maseri. They made cardiology so passionately interesting that it was easy to decide to follow that road.

My interest in intervention came a little later; it was driven by the need to actually do something myself, rather than just examine, image, analyse, and then either treat medically or refer to the surgeon. I was fortunate that the entire interventional field happened to really take off in the 80s (when I was finishing my basic cardiology training), so the timing could not have been better.

Who have been your career mentors and what was the best advice that they gave you?

Among a large number of colleagues who taught and helped me along my professional route, three figures definitely stand out: Bernhard Meier, who returned from Atlanta to Geneva in 1982 after having worked with Andreas Gruentzig; Tony Rickards with whom I worked in London in 1986–87; and Ulrich Sigwart, who was in Lausanne in 1987–88 when I was fortunate enough to be his fellow. Each of these three unique personalities has left a lasting mark in the field of intervention, and I was exceptionally fortunate to be at their side at the time I was acquiring my basic professional abilities. All three of my mentors certainly knew how to follow their convictions and disregard the taboos of their times when this was needed to cross new boundaries. They also all liked to keep thing as simple as possible; an approach that I have since tried to make my own whenever possible.

You spent one year as a research fellow in London at the National Heart Hospital. Did you see any major differences in how cardiology is practised in the UK compared with how it is practised in Switzerland?

This was in the 80s and things have changed a lot since then. At the time, coming from Switzerland, London hospitals were real gold mines for complex and rare cases, and there were a good number of brilliant minds as well. The British clinical approach was always focused and pragmatic. On the downside, resources were seriously insufficient, waiting lists absurdly long and service to the population for common ailments (like coronary artery disease!) was consequently rather insufficient.

During your career, what do you think has been the most important development in interventional cardiology?

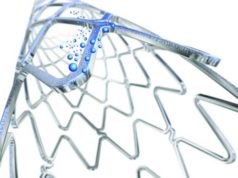

It is very difficult to pinpoint one single point in the sequence, but three elements come to my mind. First, stenting, as opposed to balloon angioplasty alone, was probably the most incredible step forward because it allowed us to fix an abrupt closure with vastly improved results compared with emergent bypass surgery. Calling the surgeon after a failed percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with an acutely occluded target vessel was a traumatic experience for all concerned, particularly the patients—they nearly always were left with a large myocardial infarction despite undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). The decrease in restenosis that came with stenting was of course also a progression, but not as decisive as ensuring an immediate stable result before leaving the lab.

Second, there has been the focus on the optimal management of acute coronary syndromes and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). It is important to remember that the pioneers in this field faced tough opposition from those who believed that intravenous thrombolysis was a far safer and more effective option than PCI with a stent. Many physicians are averse to change, and interventional cardiology has had to overcome many hurdles to obtain acceptance of what are now routine guideline-recommend therapies with a strong evidence base.

Third, the now routine use of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is an amazing achievement, and has opened the road to a vast array of structural interventions—all of which were still pure science fiction only 15 years ago. So, the future is bright!

What has been the biggest disappointment—ie. something you thought would change practice but did not?

When PCI for STEMI became established, I had high hopes for treating cardiogenic shock, and the use of left ventricular assist devices seemed a logical and important part of that strategy. Until now, however, no convincing data have emerged to justify widespread systematic left ventricular support for acute cardiogenic shock, despite several trials. Further work is needed, but the road is longer and tougher than I would have anticipated 20 years ago.

Of the research you have been involved in, what do you think has had (or will have) the biggest impact on clinical practice?

My interest in acute intervention made me realise that the best way to prevent serious myocardial infarction complications and death from heart failure is timely revascularisation to prevent (rather than to treat) haemodynamic deterioration. Therefore, contributing to the organisation of out-of-hospital management and in-hospital fast-track response for acute coronary syndrome patients was one of the most important efforts I was part of, with a direct impact on clinical practice.

My involvement in clinical trials such as MATTIS (Randomised evaluation of anticoagulation versus antiplatelet therapy after coronary stent implantation in high-risk patients: the multicentre aspirin and ticlopidine trial after intracoronary stenting), CLASSICS (the clopidogrel aspirin stent international cooperative study), or LEADERS FREE has been targeted at improving antithrombotic treatment after PCI and tailoring dual antiplatelet therapy to specific patient needs. Our community has only recently realised that bleeding is much more than a nuisance and is actually often a serious adverse event with dire consequences.

What are your current research interests?

In terms of clinical research, my main current interest revolves around the complex balance of thrombosis and bleeding in PCI patients, the value and limitations of registries in intervention, as well as the treatment and outcome of acute coronary syndrome patients admitted to Swiss hospitals.

Also, Nikesh Shreshta, a colleague interventionist and friend in eastern Nepal with whom I have been collaborating for the past eight years, and I have been analysing how acute coronary syndrome patients are treated in a developing country, how that approach differs from the one in Switzerland, and what solutions we can come up with to gradually improve the situation.

You are the medical co-director for the CERC. What does CERC do and what does your role involve?

CERC is a contract research organisation that designs and runs trials in interventional cardiology. It was founded in 2008, and is directed by Marie-Claude Morice, together with Bernard Chevalier and myself. Its expertise is based on the input from a board of distinguished interventionists from all over the world, and we currently have ongoing trials with all the main players in the field.

I contribute only in a limited fashion to the day-to-day operational activities in Paris where our offices are, although I visit on a regular basis. My role, together with Marie-Claude and Bernard, is mainly to interact with our industry partners, discuss their plans, help them design the trials they need and pick the right people to run them.

What do you consider the key research priorities in the field of interventional cardiology?

We should be devoting more time and effort to the transfer of knowledge and technology to developing countries. Non-communicable diseases are becoming a massive health problem there, and essential interventional procedures should be made more widely available despite severe logistic and budgetary difficulties.

We should (and will!) continue the spectacular voyage into structural heart disease. That domain has only just begun to open up, and there are a host of unmet needs in that area.

What has been your most memorable case and why?

A good one to choose is perhaps the first Wallstent implanted electively at the Heart Hospital in London with Tony Rickards in the summer of 1987. It was certainly my first experience of stenting and also the first coronary stent ever implanted in the UK. I had the honour of doing the femoral compression (9F sheath). The patient did well!

What advice would you give to someone who was just starting his or her career in interventional cardiology?

It is getting crowded out here, so make sure you are committed, do not count your hours, and look for the best mentor—intervention is a manual skill, not just an intellectual endeavour; you will never get anywhere without a real expert who has decided to make it their business to pass on some of their knowledge to you.

What was your childhood dream job (eg. astronaut/cowboy)?

I am sure I must at some early point have wanted to drive a fire engine, then considered becoming a ski instructor (it did not sound like work at all!), and then a banker (like my father). So, for me, medicine was a late vocation!

Outside of medicine, what are your hobbies and interests?

Skiing and hiking (with my wife Dominique, my son Michael, and friends, whenever possible). I also enjoy travelling and exploring out-of-the-way places, and we have been to India repeatedly over the past few years. Finally, serious relaxing allows me to cultivate my lazy streak and go for the three Bs: beaches, books, and the occasional bar!

Current appointment

Director of Interventional Cardiology, La Tour Hospital, Geneva

Medical co-director of the Centre for European Cardiovascular Research (CERC) in Paris, France

Chairman of the Coeur de la Tour Foundation in Geneva, Switzerland

Medical training

Research fellow in interventional cardiology with Prof U Sigwart and Prof L Kappenberger (Lausanne, Switzerland); one year

Research fellow, with Dr AF Rickards, at the National Heart Hospital in London (UK); one year

Fellow in cardiology, with Prof W Rutishauser in Geneva; two years

Senior house officer in cardiology, with Prof A Maseri and Dr C Oakley, at the Hammersmith Hospital in London (UK); six months

Surgical intensive care at the intensive care unit, with Prof D Scheidegger, of Basel University Hospital (Basel, Switzerland); one year

Internal medicine, with Prof AF Muller, at the University Hospital of Geneva (Switzerland); three years

General surgery in a Swiss peripheral hospital; one year

Main ongoing studies

The LEADERS FREE project: a randomised double blind trial of drug-coated vs. bare-metal stents in patients at high bleeding risk treated with ultra-short DAPT (principal investigator).

AMIS Registry: Swiss National Registry of patients admitted to hospital for myocardial infarction. The project is ongoing since 1997 and is endorsed by the Swiss Society of Cardiology, the Swiss Society of Internal Medicine and the Swiss Society of Intensive Medicine. Nearly 50,000 patients have been enrolled to date (steering committee member)

Prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in school children: ongoing project that has recruited 6,000 school children in East Nepal. Clinical and echocardiographic evaluation is being used to assess the prevalence of clinical and subclinical rheumatic valvular disease (co-investigator)

Societies

2011

Registered as Foreign Practitioner with the Nepal Medical Council Register

2008

Corresponding Member of the French Society of Cardiology