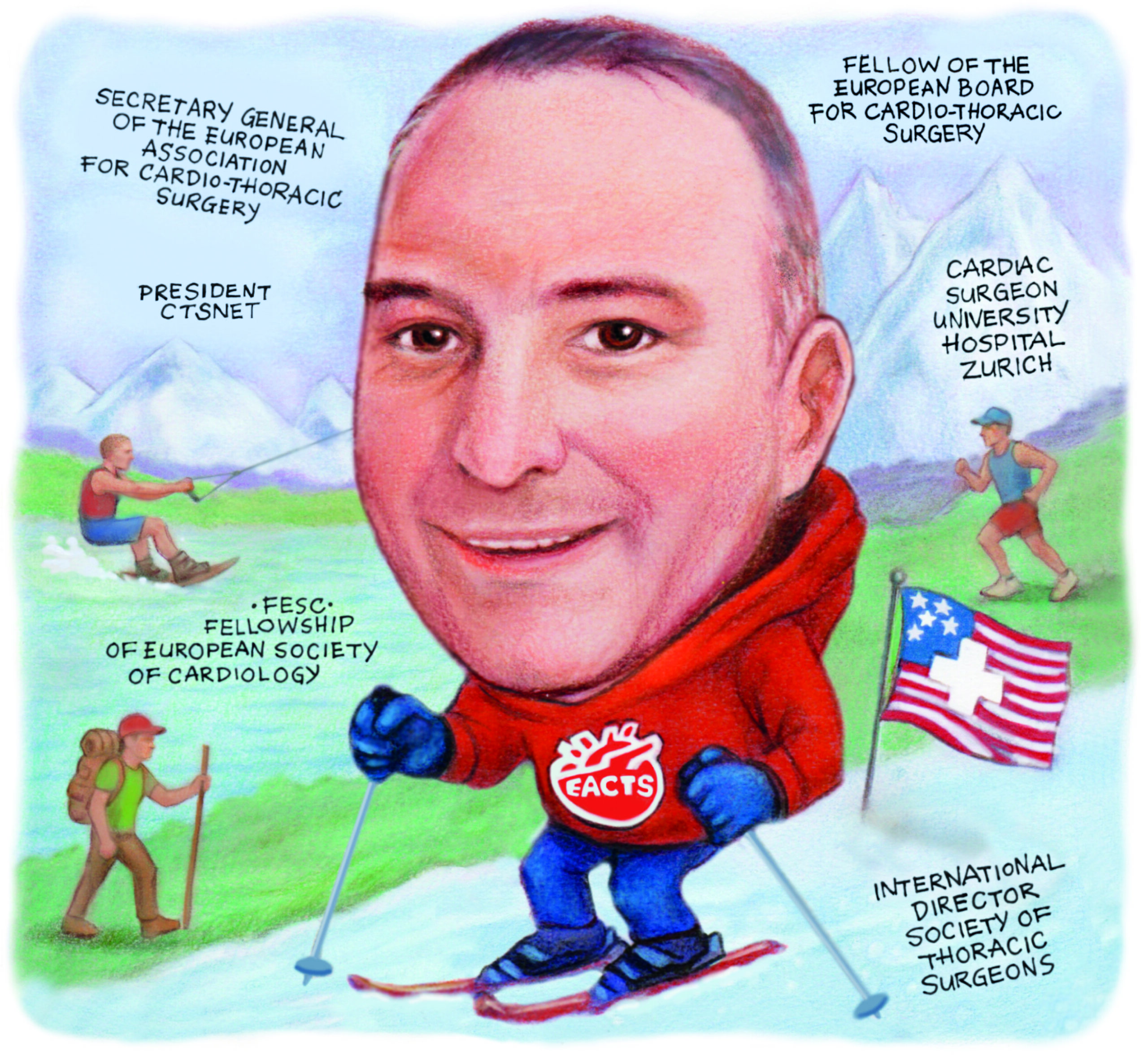

Serving as the secretary general of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) since 2022, Patrick Myers (Zurich University Hospitals, Zurich, Switzerland) has helped to steer the organisation into the post-pandemic era. In this interview he talks to Cardiovascular News about the need for more high-level trials in cardiac surgery, thawing relationships with cardiology, and future training needs for the field.

Serving as the secretary general of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) since 2022, Patrick Myers (Zurich University Hospitals, Zurich, Switzerland) has helped to steer the organisation into the post-pandemic era. In this interview he talks to Cardiovascular News about the need for more high-level trials in cardiac surgery, thawing relationships with cardiology, and future training needs for the field.

What drew you to medicine and cardiac surgery in particular?

I’ve always been passionate about understanding how the human body works, even from a very young age. When I was 11 years old, I underwent an operation which put me in contact with the medical world; it seemed natural to want to understand how

the body works and how to make things better.

Why cardiac surgery? I always did a lot of things with my hands—making model airplanes and boats, or very precisely painting Warhammer characters. Before medical school, I didn’t know what specialty I was interested in, I just knew I wanted to be a doctor. As a student I had to complete an elective working as a nurse’s aide, and I was able to go to the operating room at the end of the elective. The first procedure I saw was a pulmonary lobectomy, which I thought was interesting, but the second was a coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), and seeing the attention to detail, the precision, my immediate reaction was a big “wow, that’s for me!”.

Which mentors have shaped your career?

Training in Switzerland, I knew it was a small country and it was hard to see the full breadth of diseases and surgical techniques, so from the very start I planned to do a fellowship in the USA. Working with Larry Cohn at Brigham and Women’s Hospital was just a fantastic experience. He was a tough mentor. Being in the operating room with him was like jousting: he would push you hard, but he was waiting for you to respond, to see if you could meet or exceed his expectations. He had a big smile hidden under his mask the whole time.

After that I spent time in congenital cardiac surgery at Boston Children’s Hospital and worked with Pedro del Nido and his team. He is one of the brightest minds I’ve had the privilege of encountering—seeing how everything can be so simple when you have a mind like that is astonishing and inspiring.

How has the field of cardiac surgery changed since you began your career?

It is changing tremendously, in that we have fantastic technologies for treating coronary artery disease or treating valvular heart disease, that mean a lot of simple cases can be handled non-operatively. That makes training much harder as the complexity of surgical cases is increasing, and we have to find a way to train residents well in that.

Surgeons need to embrace these technologies. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is a fantastic technology, and I think we are currently in the euphoria phase. Adoption and indications have spread much further than the evidence supports. When I was in training, the euphoria around percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was huge and the volume of CABG was decreasing tremendously. After the SYNTAX trial was published and three-vessel and left main disease became surgical diseases again. CABG now represent more than 50% of most cardiac surgeons’ practice.

Will cardiac surgeons of the future need to master open and transcatheter skills?

Fundamentally, surgeons should be able to do both. My colleagues from vascular surgery are now vascular and endovascular surgeons. They choose which treatment modality would be the best for their patient without any conflict of interest. Cardiac surgeons need to do that and come to the heart team discussion knowing exactly the pros and cons of both options.

On the other hand, you can’t be an expert in everything. We need expertise, and this comes from intense focus. We are increasingly sub-specialising within surgery. I am mostly a coronary surgeon, but we now have heart failure, mitral valve repair, aortic surgeons, and each one of these operates in a very specialised way, at a high level. You have to be doing the same procedure all day every day to get excellent at it. I worry about saying everyone has to be able to do everything. You can’t be good at everything you do.

What can the surgical community do to adapt to the changing face of cardiovascular medicine?

Surgeons need to lead or be involved in leading these trials, which is a very different skillset to the one we have to use in our daily practice and not something you can do sustainably in parallel to a busy clinical practice. That is why my main focus in EACTS has been working with other cardiothoracic surgery associations around the world and with cardiology associations. Its fantastic that we are now invited to European Society of Cardiology (ESC) meetings and we have joint sessions at the American Heart Association (AHA) meeting, so we are really working on the heart team approach.

How has EACTS worked to build bridges between the interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery communities?

To answer that fully you have to go back to 2018/19. Most of the research surgeons were producing at the time was from single centre, observational studies, which were producing vastly underpowered, biased data comparing one modality versus another, where little causal inference could really be made. That can be important, but it is low-quality evidence and should not be guiding our practice. Surgeons were not involved in trials and didn’t understand the finesse of methodology—how to choose outcome measures, how to power a trial—but trials greatly impact our guidelines.

At the 2019 EACTS meeting in Lisbon, my predecessor, Domenico Pagano, began a trial updates session, which is now a regular Saturday morning session at our annual meeting. That started a very big controversy when the surgical principal investigator for the EXCEL trial explained that he had withdrawn his name from the trial, stating his co-investigators of dishonesty. Ultimately, that was a wake-up call and it led to us realising that, as surgeons, we can’t be on the sidelines, we have to be involved. We have to understand how these trials are designed, how they are run, how we choose outcome measures, and we are still doing that today.

Fundamentally, we all want the best for our patients and we believe in what we do. I always put in my disclosures that I am a surgeon, so obviously I am going to say surgery is best. I like Friedrich Nietzsche’s aphorism, “there are no facts, only interpretations”. We see that in guideline committees, where we can be looking at exactly the same trial but read it in a completely different way, because we read it with our biases. There is no ill intent behind that, I think we are just trying to do the best for our patients and what we believe in.

The EXCEL controversy made relations with our colleagues across the heart team a little complicated; my role has been to try and calm things down. The people I get along with the best every day at my home institution are interventional cardiologists. We help each other all the time, so why can’t we achieve that in our associations?

At the ESC congress in Madrid (29 August–1 September, Madrid, Spain) our leadership were invited to participate in major sessions there; at our annual meeting in Copenhagen (8–11 October, Copenhagen, Denmark) ESC leadership is participating actively in discussions, we have three joint sessions with European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI), which is fantastic. Even if they feel like they are going into the lion’s den—just as we feel a little nervous when we go to the cardiology meetings—we reassure them that we are here to listen, and it opens up the discussions so much.

How did you come to be involved with EACTS and how has participation in the association benefitted your career?

I started in EACTS more than 15 years ago as a resident in what used to be called the Surgical Training and Manpower committee, now the Residents’ committee. That committee was chaired by Rafael Sadaba and Matthias Siepe, the current president of EACTS and the editor-in-chief of our journal, the European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EJCTS). Along with Peyman Sardari Nia, who is the editor-in-chief of Interdisciplinary CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery (ICVTS), and a few other people who have all continued within the association, it gave us the opportunity to talk with people from all over Europe and share our perspectives, as well as get in contact with the leaders of our field and be mentored by them. In a natural way it has developed—we each contributed more and more to the association and were recruited for junior leadership roles, then leadership roles.

EACTS’ annual meeting is the largest cardiothoracic surgery meeting in the world; more than 5,000 people attend, and the buzz and interaction is fantastic. You hear the top science, but more than that, you can meet friends from all over the world—what I would dub our EACTS family.

Being a part of EACTS, you have this larger community you can rely on, and if I have a particularly complex case for an operation I don’t do routinely and I don’t have a colleague locally to whom I can refer the case, I’ll call up one of my friends in EACTS and ask them for tips and tricks, or have them give me a hand.

How attractive a specialty is cardiac surgery?

It is absolutely appealing. Over the past couple of years we have developed a Pre-trainee committee for medical students or trainees who haven’t gone into residency for cardiothoracic surgery. They are given fellowship grants to come to the meeting, to participate in different activities, and there is huge interest and engagement. I don’t think there is any specialty that can be as rewarding as one where you can actually hold your patient’s heart in your hands—it is a unique privilege and responsibility to do that.

If you talk to a layman about what we do, they are just blown away, and that is incredibly rewarding. We talk about saving lives in medicine, but if we don’t have a good result in the operating room, you see that directly and our patients suffer. It is a very big responsibility to carry; it is vastly rewarding, but it can also be a very tough specialty. As René Lerich said, “every surgeon carries a cemetery in their heart, for patients lost”.

Which has been the most impactful recent research paper you have read?

If I have to pick one, it’s one that hasn’t been published yet—the 10-year results of the PARTNER 2A trial, comparing TAVI versus SAVR [surgical aortic valve replacement] in intermediate-risk patients. This was published on the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website, and it shows there is a survival benefit at 10 years of SAVR over TAVI.

This is what we have been saying as a surgical group; the operations we do carry an initial hazard, even if we do a minimally invasive procedure it takes time to recover from that, and for a patient, psychologically, it is maximally invasive so you have to have a very good reason to do it. Many of the trials have short-term follow-up. What we tell our patients is the reason we pick CABG or SAVR over percutaneous options is because they have an expected survival that is 10 years or more, and the benefit of our treatments show during this long follow-up. Our trials need to have long-term follow-up, but most of the TAVI versus SAVR trials have only published five-year results.

The very long-term results we have only come from one trial, NOTION, which is in very elderly patients with surgical valves which are off the market now because of their early degeneration, so the only prospective randomised data that we have out there says that there is no difference at 10 years.

What is interesting to me about the PARTNER 2A results is—even if it is an older patient population with a lot of competing risks, and over 80% of the patients passed away at 10 years—there is a difference between the groups and SAVR does have better long-term survival.

What does your life outside of medicine look like?

I’ve got two children, who are 17 and 15. Living in Switzerland, I have access to mountains for hiking and skiing, and sailing on the lakes. I’m an avid runner, I run three to four half marathons per year. If ever I am in New York, I love running in Central Park—where you have the ultramarathoner who is running circles around everybody at a blistering pace, and someone much less fit, going very slowly but happy they are out doing it. Seeing that reminds me that we are each running our own race—against ourselves.

I love the expression from George Bernard Shaw: ‘We don’t stop playing because we grow old, we grow old because we stop playing’. After years of skiing and snowboarding, this summer I started wakeboarding—and it’s fantastic.