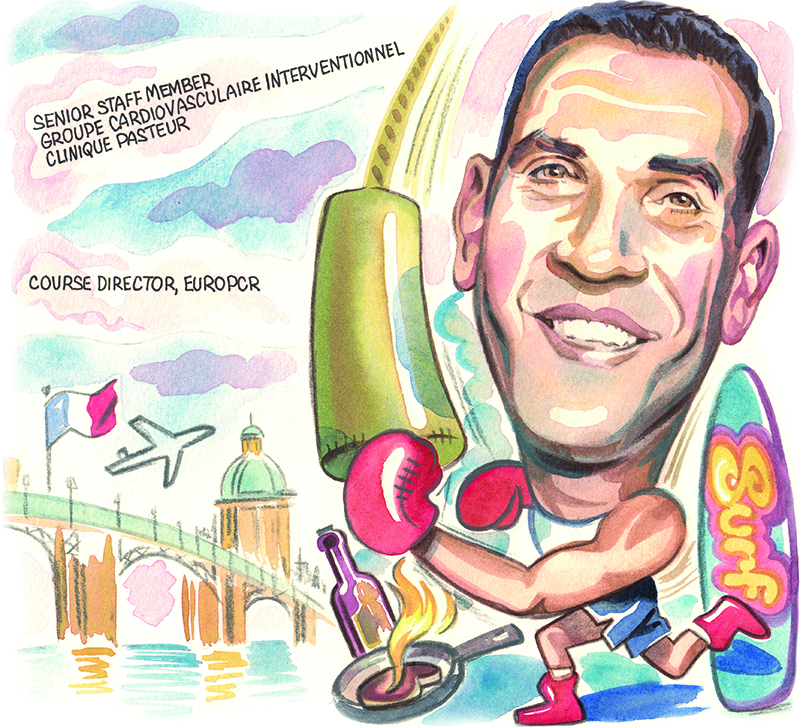

Medicine and indeed interventional cardiology were not initially on the radar for Nicolas Dumonteil (Clinique Pasteur, Toulouse, France), but he was attracted into the field by the dynamism of the interventionists he encountered during his early career. With a keen interest in structural heart interventions, Dumonteil is well known for his work in transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) and is also a course director for the EuroPCR meeting. He spoke to Cardiovascular News about his expectations for the evolution of the field, and what to look out for at EuroPCR 2024.

What drew you initially to medicine and why did you decide to become an interventional cardiologist?

Medicine was not something I had thought about when I was young, my real passion was aeroplanes and aviation. I was able to fly a plane before I was legally allowed to drive a car, and initially I wanted to become a commercial pilot but that did not work out. After that I thought about pursuing a career that could have some intellectual interest for me, and I decided to change direction towards medicine.

Then I tried medical school, and I liked it. The choice of interventional cardiology came later. I had to choose between becoming a general practitioner or a specialist and my choice was mainly influenced by the fact that the interventional cardiology department at the university hospital I was in at the time was very dynamic. I had good examples of senior physicians showing how they enjoyed their work, and that is why I went in that direction, without really knowing that it would be something that I would do for the rest of

my life.

Who have been the biggest influences on your career?

There are three names who come to mind at different stages of my career. While I was a medical student a colleague who is not at all known in the field of interventional cardiology, Bruno Francois, an anaesthesiologist, was the first person I really admired for his high levels of medical knowledge, skill, empathy with patients, and also for the relationship I developed with him as a mentor. That helped me to trust myself and gain confidence in pursuing this career.

When I became an interventional cardiologist at the University Hospital in Toulouse and was a really young member of the team, my boss, Professor Didier Carrié, gave me the opportunity to develop the TAVI programme. When I look at what I am doing in meetings or my publications, I would not have gone down this path without this.

The third person to mention is Jean Fajadet of the Clinic Pasteur group. Some years after I decided to move from the University Hospital, he was the one who welcomed me and opened up the PCR universe and helped me to engage myself in this organisation.

What has been the biggest change in the field of interventional cardiology since you began practicing?

It was total luck that I became a senior interventional cardiologist in the University Hospital staff around 2006, not long after Alain Cribier did the first-in-man TAVI case in 2002. At that time TAVI was only in Rouen, and then it started to develop in other countries. I had the chance to start my career at that period and to develop the TAVI programme at my hospital.

Have there been any disappointments?

I took some time to think about this, and also took a poll with my colleagues. I think the first reply that came from everybody was bioresorbable vascular scaffolds. When it first appeared, it was seen as a revolution in the coronary part of interventional cardiology, but at the end of the day it was a huge disappointment. I don’t think that the story is over, and the concept is still there, but the devices that were proposed in the first or second generations were not mature enough. However, we have new devices coming now that continue this concept and I think that some of those are promising.

What is the current area of focus of your research?

In my general practice I am quite polyvalent, but from a scientific standpoint I focus mainly on structural parts of the interventional cardiology field and mostly on TAVI. My major point of interest currently, which I would also say is a point of concern, is the TAVI-in-TAVI pathway and the lifetime management of patients with aortic stenosis—the option to treat a patient from the first intervention with a transcatheter aortic valve, and then in case of degeneration, come back with a new transcatheter option.

Perhaps the community went a little too fast in adopting TAVI for really young patients with long life expectancy. I was a part of that 15 years ago believing that if the valve degenerates, we will come back with a new TAVI, but we are currently learning that it is not so simple. I think we have some work to do to educate the community on that.

A lot of this is patient anatomy driven. We need to explain to the community that if you want to treat patients with long life expectancy who will probably outlive their first TAVI implant, from the planning of the first intervention you have to anticipate the potential second one. If you think that the second intervention might not be possible then perhaps you should change direction towards surgery.

How will interventional cardiology evolve in the next decade?

It is always difficult to predict the future, but we are already seeing an important shift towards the structural part of interventional cardiology, in particular valvular interventions. While the coronary field is not shrinking, it is getting quite stable, and we have more and more robust evidence showing that percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) saves lives in the context of acute coronary syndrome, while for chronic coronary syndrome, it is more for symptom improvement, and so the potential for development is smaller. On the valvular side, TAVI has opened the door, and we are seeing development in mitral and tricuspid technologies. If I had to bet, I would put more money on tricuspid techniques coming through than on mitral.

Which trials have caught your attention in the last 12 months?

I would say that the TRILUMINATE randomised trial has been important because it was the first of its kind to demonstrate that a tricuspid repair device positively impacted the lives of patients by improving their quality of life over optimal medical therapy. It has opened the way for transcatheter therapy on the tricuspid side, and many other studies are enrolling or about to be published. A similar trial performed in France, Tri.fr, will be reported this year at the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) meeting (30 August–2 September, London, UK).

What is it about EuroPCR that makes it a unique meeting?

PCR has a mantra, that it is ‘by and for’, meaning that everything is made by the interventional cardiology community to share knowledge, experience and practice, for the needs of the physicians, wherever they are from, and also for the patients’ needs. You can share experience and learn by watching live cases being done in selected centres, by going to sessions where you are able to learn techniques from A–Z, or by going to case-based sessions where you are going to learn how to manage complications.

What can attendees expect from EuroPCR 2024?

This year there will be a focus on the crucial role of imaging to guide cardiovascular interventions. Without X-ray guidance interventional cardiology would not exist, and while we started from having only this imaging tool in the early ages, now when I look at what I am doing in a single day, I use different imaging modalities for any intervention. It starts with ultrasound guidance for vascular puncture, then you have the computed tomography (CT) analysis to plan your intervention. You have X-ray guidance integrated with artificial intelligence (AI), physiology information, and procedural echocardiography guidance. Imaging is everywhere and it is for the benefit of our patients. If outcomes have improved over the years, it is because we understand how to guide our interventions more accurately with imaging.

This will be a recurrent and common theme throughout the programme, and we will have an imaging learning centre, a dedicated space for learning about intracoronary imaging in different anatomical situations and also imaging for structural interventions.

Does interventional cardiology need to do anything differently to attract and keep young doctors?

This is a specialty that is very attractive for young colleagues, and we do not currently have a lot of concerns about low attractivity. But I think as a community we have to do better to attract and keep women in the field.

Thinking about the environment I was trained in 25 years ago, there was a lot of male chauvinism and this specialty was not welcoming for female colleagues. Although that has evolved in a positive way, we still have to keep this spirit ongoing and also to keep on improving conditions for our female colleagues. When you are an interventional cardiologist, pregnancy can be a real issue, and we have to improve that. I feel personally engaged in that, my wife is a physician and had to struggle a lot to simply keep on doing her job when she was pregnant. As a father to two daughters, I would like that if they were interested in becoming interventional cardiologists, they do not experience any kind of limitation because they are female.

Looking back over your career, are there any memorable cases that stand out?

I had the opportunity to treat both a husband and wife with an innovative device, the Tendyne mitral valve replacement device (Abbott). I treated the husband during the early stages of the development of the valve, in the context of a clinical study. The procedure went well, and the patient was really positively transformed by the procedure in terms of quality of life. Then, some years later, his wife required the same kind of intervention, and the nice thing about it was that the husband had explained everything to her, so she arrived at the intervention really relaxed and confident, even though she was in a really critical medical state. She was also really positively transformed by the outcome of the intervention, and they were able to live their life together for some years after, which would not have been possible without the procedure.

What are your hobbies and interests outside of medicine?

As soon as I am outside of work, I try to dedicate as much time to my family as I possibly can. Sport is also a very important part of my life—I used to play rugby when I was younger, but as you are getting older it is not something that you can keep doing! More than 10 years ago I found English boxing as a substitute, as it has the same level of intensity as rugby.

Something I like to do to spend time with my kids is surfing. It is hard, but I like it! I am still at the stage where I am struggling, but when I catch a good wave, it can make my day, week or even my year.

I also really enjoy cooking, and I believe that is another important family activity. I like to train my kids in how to cook. French cooking is quite rich, you have a lot of recipes to go through. When you can spend one or two hours preparing a meal and see the whole family participating in that and enjoying that, it is nice and I think it is an important part of our culture, and I want my kids to enjoy that. It is also a way for them to learn how to take care of themselves, preparing fresh food and cooking.