While the exact location of atherosclerotic plaque ruptures—a common cause of myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke—has previously been unknown, researchers at Lund University (Lund, Sweden) have now managed to successfully map this phenomenon. In addition, the team has identified an enzyme that they hope will act as a marker to help predict who is at risk of having an MI or stroke due to ruptured atherosclerotic plaque.

While the exact location of atherosclerotic plaque ruptures—a common cause of myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke—has previously been unknown, researchers at Lund University (Lund, Sweden) have now managed to successfully map this phenomenon. In addition, the team has identified an enzyme that they hope will act as a marker to help predict who is at risk of having an MI or stroke due to ruptured atherosclerotic plaque.

“In our study, we were able to pinpoint exactly where plaques rupture,” said Isabel Goncalves (Lund University, Lund, Sweden), who led the study. “This is an important step, allowing for a better understanding of why they rupture. Previous studies have focused more on how plaques are formed while we have studied the precise area where they rupture, which no previous human study has done.”

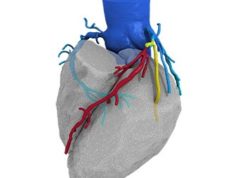

Goncalves and colleagues’ research indicates that atherosclerotic plaques in the carotid arteries often rupture at the beginning of the plaque—at a location closest to the heart. The study in question has now been published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC).

Important patient groups

This research is based on studies of atherosclerotic plaques in the carotid arteries from a total of 188 patients. The researchers used electron microscope and ribonucleic acid (RNA) sequencing techniques to get a detailed picture of the location where most plaques rupture. High blood pressure and type 2 diabetes are factors that increase the risk of atherosclerosis and, therefore, these patient groups were also included in the study.

“One of the strengths of our study is that it is based on a close collaboration between clinically active researchers and experts in bioinformatics,” stated Jiangming Sun (Lund University, Lund, Sweden), first author of the paper. “We have also used several different techniques to allow as detailed analyses as possible. It was important [for] us to include people with type 2 diabetes in the study as this is a group with high risk of dying from complications related to atherosclerosis compared to the rest of the population.”

Marker for complications

The RNA sequencing showed a strong association between the enzyme matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and the area where plaques rupture. High levels of MMP-9 could also be associated with an increased risk of future cardiovascular disease in individuals with atherosclerosis. The researchers hope to be able to use MMP-9 as a marker to predict which patients are at risk of having an MI or a stroke. They are also investigating if it is possible to develop new treatments that reduce the risk of plaque rupture.

“Our study shows that MMP-9 is a marker of future cardiovascular complications,” added Goncalves. “In further studies, we want to investigate if it is possible to inhibit the enzyme, so it becomes less active, and thus prevent plaque rupture. However, it is important that such treatment does not lead to unwanted side-effects as the enzyme has other important functions in the body.”

Preventive measures

For several years, Goncalves has worked to learn more about what happens when plaques rupture, together with her clinically active research colleague Andreas Edsfeldt (Lund University, Lund, Sweden). As practising physicians—both at Skåne University Hospital in Malmö, Sweden—Goncalves and Edsfeldt see a lot of patients they would like to help at an earlier stage than what is possible today.

“We see a lot of patients who have had a heart attack or have become partially paralysed following a stroke and can no longer live life as they used to,” Goncalves continued. “Often, atherosclerosis does not cause symptoms at an early stage, so it can take years before the disease is noticed. Sadly, those of us who work clinically discover the plaque too late, when it has already ruptured and caused serious complications like sudden death, heart attack or a stroke. If we can learn more about the underlying mechanisms, we can initiate preventive measures or treat the dangerous plaques in time.”