Quitting methamphetamine use can reverse the damage the drug causes to the heart and improve heart function in abusers when combined with appropriate medical treatment, potentially preventing future drug-related cases of heart failure or other worse outcomes, according to a study published in JACC: Heart Failure.

“The work presented emphasises the fact that the growing drug epidemic will have long term cardiovascular consequences in addition to the known short-term tragic events ,” says editor-in-chief of the journal, Christopher O’Connor.

Methamphetamines—commonly known as crystal meth—are one of the most frequently used drugs worldwide, and previous studies have shown that heart-related issues are commonly a factor in death from methamphetamine use. While medical treatments are available for these heart conditions, there is little information about if heart damage can be improved or reversed by discontinuing the drug abuse.

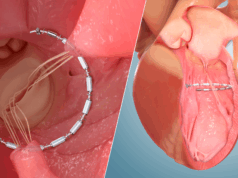

Researchers looked at 30 patients abusing methamphetamines to assess if heart function improved after discontinuing methamphetamine use. Patients were on average 30 years old and over 93% were male. All had a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 40%, which is considered evidence of heart failure. Over 83% were highly symptomatic and suffered from laboured breathing. One-third also developed intracardiac thrombi, or blood clots.

All patients received medical treatment including supportive measures and guideline-supported medical therapy, which included automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator or wearable cardioverter-defibrillator in some patients. Symptoms and cardiac function improved significantly in patients who discontinued methamphetamine use. Also, patients who discontinued the drugs had a lower incidence of the primary endpoint of death, non-fatal stroke and rehospitalisation for heart failure versus those who continued the abuse methamphetamines while on medical therapy, 57% vs. 13%, respectively.

“Methamphetamine associated cardiac myopathy will become a growing cause of heart failure in young adults,” says Norman Mangner, senior author on the study and a physician at the Heart Center Leipzig in Leipzig, Germany. “Due to the chance to recover cardiac function and symptoms at an early stage of the disease, early detection of heart problems in patients with methamphetamine abuse could prevent further deterioration of the cardiomyopathy.”

The study did have limitations, including the possibility for non-compliance to medical therapy. Also, only patients with heart failure and severely impaired cardiac function were included, so there is no information on the evolution of heart problems caused by methamphetamine use and possible early, asymptomatic phases.

In an accompanying editorial, James L Januzzi, Hutter Family Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston, USA, said the study provides objective data showing that in methamphetamine abusers, cardiac function will only improve after they quit using the drugs, and these findings should impact the treatment plan.

“Rather than simply placing patients with suspected methamphetamine associated cardiomyopathy on a cocktail of neurohormonal blockade, the majority of focus should be on helping such patients quit,” he says.