Francesco Maisano (University Heart Centre, University Hospital Zurich Zurich, Switzerland) works on the border between surgery and interventions; he embraces heart team challenges and opportunities. He talks to Cardiovascular News about how life has had an influence on his career and how mentors and friends helped him to become an innovator and pioneer in the field of transcatheter valve interventions.

Who and what inspired you to become an interventional cardiologist?

I decided to go into medicine because I had an example in my family—my father was an old-style general surgeon. He was one of those surgeons who could perform almost any operation, ranging from caesareans, thorax surgery, to amputations, gastrectomy, and skull perforation. I think this model was important to me in my career. The reason why I wanted to become like him is because of how he treated his patients. He was not rich, but all of his patients became friends; he worked in small village and he had a patient in every house of that village.

After initially wanting to be a biologist, because I thought I would have a better quality of life (my father was always working), I decided that I wanted to be a surgeon and my dream was to become a general surgeon, like my father. However, my father had an extensive anterior myocardial infarction, followed by incessant image result for ventricular tachycardia. The problem was apparently impossible to manage and, therefore, it was decided to transfer him to The Netherlands where an expert in the field of surgical treatment of arrhythmias could try to manage the issue. As a young medical student, and a scared young son (I was 21 at that time), I felt this was the only chance, and I was hopeful that my father would survive. I flew with him and I met the professor who could save the life of my father.

When I entered the room, I was looking for somebody older; a wise man, somebody with a long white beard. I kept on looking in the room to see if there was such a figure but then, not without surprise, a man—Ottavio Alfieri—who was not yet 40 introduced himself. Upon meeting him, I had a mixed feeling of disappointment and curiosity. However, this young man was already such a star. It was late 80s—a time when cardiac surgeons were divine beings, second only to God (outside of the operating room… ). This was my first encounter with the man who was to change my life.

He decided not to operate on my father, and the ventricular tachycardia was treated with amiodarone (a relatively new drug at that time). This was the first lesson that I still bring with me… what makes a great interventionalist, is not how we do things, but how we make the right decision.

One day I saw Alfieri performing an open heart surgery. This was the day that signalled the direction of my life. I saw the heart beating, and then the cross-clamping, and the magic cardioplegia. The heart was standing still, and Alfieri could do a lima-left anterior descending anastomosis. Then, the heart was reperfused, and then came even more magic: the heart start beating again! It was too much, too incredible, and too impossible. I knew then I wanted to be a cardiac surgeon. I was fascinated by heart physiology and to the possibility of mechanically intervention to improve heart function.

How did you go from wanting to be a cardiac surgeon to becoming fully qualified?

I started my residency in Rome and then I managed to continue my studies in Brescia, with Alfieri. In 1993, I spent one year in Alabama where I met a lot of international fellows, and I had the privilege of working with the late John W Kirklin, his son James Kirklin, and with Albert Pacifico.

Coming back to Italy, in 1995, I was awarded the certification in the cardiac surgery speciality and got a position as staff surgeon in Alfieri’s centre. At that time, I thought this was the end of my training. Wrong! It was only the beginning.

What were your interests in the early stages of your career?

Initially I was interested in two areas: mitral repair and off-pump bypass surgery. In the field of mitral valve repair, I invented a new ring concept, together with Alfieri, which was then sold to Edwards Lifesciences and resulted in the commercialisation of the Ethilogix family of Edwards functional mitral regurgitation rings (Geoform and IMR). In parallel, I developed an interest in learning how to perform percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) as I wanted to expand the possibilities of treating patients with multivessel disease undergoing CABG. It was the beginning of the “transformation”.

In 1998, my main focus was still surgical mitral repair. At this time, I published a paper on the Alfieri technique, which for the first time stated that this technique simplified mitral repair so much that it could be applied to develop a catheter-based approach to mitral repair. Soon after, I was involved in developing an off-pump device to perform the Alfieri procedure. It was a suction and suture device for a trans-atrial suture-based Alfieri repair; the implant was done under echo guidance, the device was developed by Edwards, and it looked like a pistol gun. During this time, I learnt the basic of preclinical research and the challenges of developing new procedures. This was the beginning of a long story, the beginning of catheter-based mitral interventions. Soon I met an engineer that showed me a 12Fr catheter that could perform the same as the surgical prototype. I had no doubts: this was the future, and I wanted to be part of it. Immediately, I went to Antonio Colombo and started my cross-training in interventional cardiology. This was the beginning of the most transformational experience of my full life. I had the opportunity of seeing the challenges and opportunities of collaboration between surgeons and interventional cardiologists. Today I am the least biased physician! I can perform and fully appreciate benefits and limitations of surgical and interventional treatments, and deliver the best treatment to my patients.

What has been the most important development in interventional cardiology during your career?

I have been active part of the development of valve transcatheter interventions—particularly mitral—but I have also participated in the development of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). I have performed as first operator or assisted junior operators more in than 1,500 TAVI procedures. Later I dedicated a lot of time on mitral interventions, developing some new techniques and technologies. In this effort, I met a number of great cardiologists and surgeons who became partners, friends, and mentors. The list is too long, but I would like to mention Ted Feldman, Alec Vahanian, Maurice Buchbinder, Karl Heinz Kuck, Mike Mack, Jose Pomar, Marty Leon, Patrick Serruys among many others. They all contributed to what I am today.

Over the last 10 years, I have trained hundreds of physicians and helped some surgeons to become cross-trained in interventional cardiology. I have been one of the pioneers in the field; Marty Leon often uses my work to describe the evolution of structural interventions.

What has been the biggest disappointment? For example, something you thought would change clinical practice but did not?

I believe that mitral valve interventions can save lives in heart failure patients, but only if we can apply the therapy early enough. I wish I was able to find an industry partner who wanted to invest time and resources to help me demonstrate this in a properly designed clinical trial.

Of the research you have been involved with, what do you think has had the biggest impact on clinical practice?

The introduction of percutaneous edge-to-edge repair (MitraClip, Abbott Vascular) in clinical practice in Europe (ACCESS registry) and the development of Cardioband (Valtech/Edwards Lifesciences). Cardioband is the first catheter-based technique that closely resembles a surgical annuloplasty.

At the moment, I am now dedicated to the field of transcatheter mitral replacement, new tissue material for structural interventions, and… something else that I am not a liberty to discuss!

What are advantages and disadvantages of MitraClip and percutaneous annuloplasty?

MitraClip remains the gold standard at this time; it has accumulated data for 50,000 patients with >10 years follow-up. It is very versatile, and can be applied to most patients with mitral regurgitation. However, double orifice technique might induce an increase in gradients and in mean left atrial pressure: this issue is probably underestimated.

Annuloplasty, on the other hand has a very strong background. It is the most commonly performed surgical procedure for mitral valve repair as a stand-alone solution in case of functional mitral regurgitation and as a complementary therapy to leaflet repair in degenerative mitral repair.

Compared with MitraClip and with surgical mitral replacement, percutaneous annuloplasty is more respectful of anatomy and physiology of the mitral valve. Also, the implant of annuloplasty is more straightforward than a MitraClip implant—it is a pure anatomical procedure (same strategy and technique for all patients) with no interference with the leaflets (no risk of damage, distortion, etc.)

You are also involved in evaluating a transcatheter approach for managing tricuspid regurgitation. What are the challenges of developing such an approach?

I performed the first tricuspid repair intervention in the world. For that we used a device that I have developed—the Tricinch (4Tech). The challenges for tricuspid are many. It is a completely new environment, with new imaging challenges, as well as unclear navigation. The main challenge remains patient selection, particularly today when there are many options.

I have also performed the first-in-human Cardioband tricuspid repair. This was less of a challenge than I predicted it would be. The procedure is somehow easier than others. In particular, compared with leaflet repair, annuloplasty seems to be easier. An important advantage is imaging, since imaging leaflets is not easy with transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) in many patients, identifying the annulus seems simpler.

What is the “ideal” heart team for transcatheter heart valve therapies?

I have been part of the heart team since its very beginning. There are many kinds of heart team, depending on local situation. Regardless of the specific details, a good functioning heart team should be based on competence and respect of others. The modern physicians should be competent in a field of cardiovascular medicine rather than be defined by his/her technical skills. It is not anymore possible to be like my father, a surgeon who could operate all organs of the body. Today we need super-specialists who master the overall patient track as well as are able to deliver (eventually in team) the full spectrum of therapies.

The problem is that although the heart team is a good concept, there is lack of education about it. The physicians, at the moment, are not ready to work in teams. This is why we initiated a course for heart team members in Zurich. With this course, clinical competence education is fused with leadership courses and innovation training. Additionally, I organise the Mitral Valve Meeting (5–7 February, Zurich, Switzerland). This is a great gathering, with about 800 experts in the field attending, that has become a place to share ideas and be inspired.

What has been your most memorable case and why?

I have a lot of them! I remember each first-in-human, every live cases, all the challenging cases, and all complicated cases. In particular, in the case of complications, I have always learned something: what to do, what not to do, how to avoid complications, how to bailout, and how to solve complications.

But if I have to choose one, I take the first-in-human Cardioband procedure. After five years of development and more than 200 animals, we knew a lot of things, but still we had a number of uncertainties. The case took more than three hours. We had to learn echo imaging guidance (all animal procedure were performed with transapical intracardiac echocardiography while the first-in-human used TOE), but at the end, the implant was successfully obtained. I still remember the excitement of seeing mitral regurgitation disappearing while cinching the annulus. I had at that time already experience with MitraClip, but I had never seen before a complete abolition of mitral regurgitation with a catheter approach.

What are you hobbies and interests?

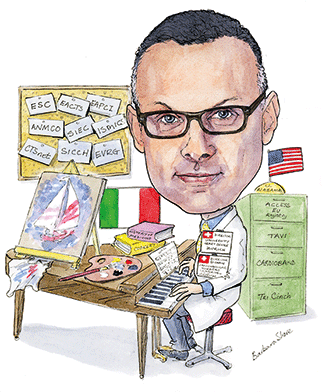

I play piano, I paint, I sail, I cook, I like history books, and I love medicine!

Factfile

Current appointments

- Director of the University Heart Center of Zurich

- Director and Chair Cardiovascular Surgery, University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Previous appointments

- 2013–2014: Director of Transcatheter Valve Treatment programme, University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

- 2009–2013: Director of Transcatheter Valve Treatment programme, SanRaffaele University Hospital, Milan, Italy

- 1997–2009: Staff heart surgeon, San Raffaele University Hospital, Milan, Italy

Education and academic qualifications

- 2014: Appointed professor for Cardiac Surgery, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

- 1995: Cardiac surgery license—thesis: “Surgery for severe left ventricular dysfunction”, University of Rome, Università La Sapienza, Rome, Italy

- 1994: Special postgraduate fellowship, University of Alabama, Birmingham, USA

- 1990: MD—thesis: “Parenteral nutrition in the intensive care unit”, University of Rome – Catholic University of the Holy Heart, Rome, Italy

Professional society membership

- European Society of Cardiology (ESC)

- European Association of Cardiothoracic Surgery (EACTS)

- European Association of Percutaneous Coronary Interventions (EAPCI)

- National Association of Physician Cardiologist (ANMCO)

- Italian Society of Cardiovascular Echography (SIEC)

Major scientific achievements

- The principal investigator of the ACCESS EU registry, the largest European registry monitoring the real-world results of MitraClip therapy

- Co-inventor of a surgical annular prosthesis, which today represents a standard surgical technique for the treatment of functional mitral regurgitation

- The development and introduction in clinical practice of the first ever catheter-based, surgical-like, direct annuloplasty (Cardioband) for the heart valves

- The development of the first worldwide transcatheter device to repair the tricuspid valve, the TriCinch system

Prof. Maisano, MD., politechnichal surgeon, is exemplarily moving medicine forward and today amongst greatest assets of cardiac surgery development. Many will benefit from his work this far… more to come…

Amazing talent, huge work capability, so succes for sure. A pioneer in the revolution of the new cardiovascular treatment. It seems incredible how, with examples like Professor Maisano, still there are people that are not able to see the way. We need this sort of leadership in cardiac surgical community and professional associations.Full admiration for him.

Times they are a-changing.

Fully deserved. Congratulations

Admirable human being!

In addition to being an exceptional physician