Five-year results of the FAME 3 trial, comparing fractional flow reserve (FFR)-guided percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery in patients with three-vessel coronary artery disease, have shown no significant difference between the two strategies for a composite outcome of death, stroke or myocardial infarction (MI).

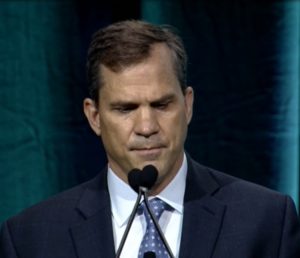

Previously, PCI had failed to meet the primary endpoint of non-inferiority versus CABG with respect to the composite of death, stroke, MI or repeat revascularisation, however, presenting the five-year findings at the 2025 American College of Cardiology (ACC) scientific session (29–31 March, Chicago, USA), William Fearon (Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, USA) commented that the difference in outcomes had narrowed at five years likely due to improved stent technology, routine application of FFR-guided PCI and greater adherence to guideline-directed medical therapy. Findings of the study were also published in The Lancet.

The FAME-3 trial enrolled 1,500 patients in North America, Europe, Asia and Australia. The patients’ average age was 65, 82% were men—reflecting the disease’s predominance in men, Fearon said—and 93% were White. To be eligible for the study, patients had to have blockages of at least 50% in three of the major arteries supplying blood to the heart, but no blockages in the left main coronary artery.

Nearly four in 10 of the enrolled patients had been hospitalised with a heart attack or unstable angina, and nearly one in five had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

Patients were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups. Those assigned to CABG underwent bypass surgery. Those assigned to the second group first had FFR measured; only narrowed arteries with an FFR score of 0.8 or less underwent PCI to place a drug-eluting stent (DES).

After the procedure, these patients also took two medications for at least six months to reduce the risk of a heart attack, stroke or blood clot. Blockages with FFR scores above 0.8 did not undergo PCI but were treated with medicine. All patients enrolled in the study received guideline-recommended medical treatment for their heart disease, including aspirin, statins and other medicines as needed.

All patients were followed in the hospital and at 30 days, six months, and one, two, three and five years after treatment. For the one-year follow-up, the study’s primary endpoint was a composite of death from any cause, stroke, heart attack or need for a repeat procedure.

For the three- and five-year follow-ups, the primary endpoint was a composite of death from any cause, stroke or heart attack. The trial was designed to determine, at one year of follow-up and with over 90% probability, the non-inferiority of PCI, compared with CABG, on meeting the study’s primary endpoint.

Almost 95% of patients completed five years of follow-up. At the five-year analysis, more than 90% of patients in both treatment groups were taking an antiplatelet medication to prevent blood clots. A similar percentage were taking a statin to reduce blood levels of “bad” cholesterol. In addition, more than 70% were taking a beta blocker to control irregular heart rhythms and blood pressure and a similar percentage were taking a medication to reduce strain on the heart by lowering blood pressure and prevent or manage heart failure or kidney disease.

No significant difference was seen between patients assigned to PCI or CABG on the composite endpoint. When each component of the composite endpoint was analysed separately, death rates were identical in the two groups (7.2%) and rates of stroke (PCI, 1.9%; CABG, 3%) were not significantly different. However, more heart attacks occurred in patients assigned to PCI (8.2%) compared with CABG (5.3%). Patients treated with PCI also needed more repeat procedures than those treated with CABG (15.6% vs. 7.8%).

A possible limitation of the study is that only 12% of patients treated with PCI received intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), Fearon said.