An anticancer agent in development has been shown to promote regeneration of damaged heart muscle—an unexpected research finding that may help prevent congestive heart failure in the future.

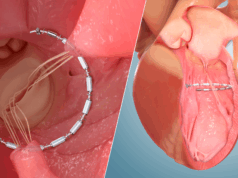

Many parts of the body, such as blood cells and the lining of the gut, continuously renew throughout life. Others, such as the heart, do not. Because of the heart’s inability to repair itself, damage caused by a heart attack causes permanent scarring that frequently results in serious weakening of the heart, known as heart failure.

For years, Lawrence Lum, associate professor of Cell Biology at UT Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW; Dallas, USA), has worked to develop a cancer drug targeting Wnt signalling molecules. These molecules are crucial for tissue regeneration, but also frequently contribute to cancer. Essential to the production of Wnt proteins in humans is the porcupine (Porcn) enzyme, so-named because fruit fly embryos lacking this gene resemble a porcupine. In testing the porcupine inhibitor researchers developed, they noted a curiosity.

“We saw many predictable adverse effects—in bone and hair, for example—but one surprise was that the number of dividing cardiomyocytes (heart muscle cells) was slightly increased,” says Lum, senior author of the paper, and a member of UTSW’s Hamon Center for Regenerative Science and Medicine. “In addition to the intense interest in porcupine inhibitors as anticancer agents, this research shows that such agents could be useful in regenerative medicine.”

Based on their initial results, the researchers induced heart attacks in mice and then treated them with a porcupine inhibitor. Their hearts’ ability to pump blood improved by nearly twofold compared to untreated animals.

The study findings were published online in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Our lab has been studying heart repair for several years, and it was striking to see that administration of a Wnt inhibitor significantly improved heart function following a heart attack in mice,” says Rhonda Bassel-Duby, professor of Molecular Biology and associate director of the Hamon Center for Regenerative Science and Medicine at UTSW.

Importantly, in addition to the improved pumping ability of hearts in the mice, the researchers noticed a reduction in fibrosis, or scarring in the hearts. Collagen-laden scarring that occurs following a heart attack can cause the heart to inappropriately increase in size, and lead to heart failure.

“While fibrotic responses may be immediately beneficial, they can overwhelm the ability of the heart to regenerate in the long run. We think we have an agent that can temper this fibrotic response, thus improving wound healing of the heart,” says Lum, a Virginia Murchison Linthicum Scholar in Medical Research and associate director of Basic Research at the Harold C Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center (UTSW).

Additionally, Lum says, preliminary experiments indicate that the porcupine inhibitor would only need to be used for a short time following a heart attack, suggesting that the unpleasant side effects typically caused by cancer drugs might be avoided.

“We hope to advance a Porcn inhibitor into clinical testing as a regenerative agent for heart disease within the next year,” Lum says.