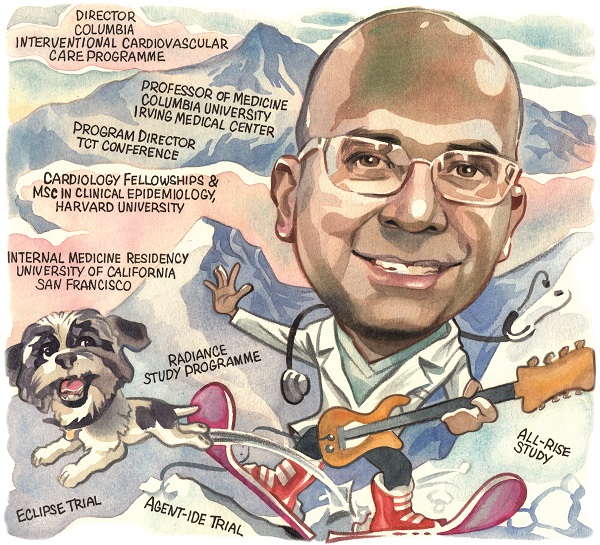

For Ajay Kirtane (Columbia University Irving Medical Center/NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, New York, USA), success in medicine involves marrying a humanistic approach to care with a thorough understanding of clinical data. An accomplished trialist, physician and educator, he tells Cardiovascular News about his career and expectations for the future of interventional cardiology.

For Ajay Kirtane (Columbia University Irving Medical Center/NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, New York, USA), success in medicine involves marrying a humanistic approach to care with a thorough understanding of clinical data. An accomplished trialist, physician and educator, he tells Cardiovascular News about his career and expectations for the future of interventional cardiology.

Why did you choose to become an interventional cardiologist?

Don’t all Indian-Americans aspire to become interventional cardiologists?! To be honest, I was actually somewhat anti-medicine growing up because, as an Indian-American, it is quite common to follow your parents into medicine or engineering. I am really thankful that my parents did not push me overtly in that direction. I was interested in the biological sciences and was on the path to doing a PhD, but ultimately I missed the absence of human interaction in the lab.

I’ve always thought that the biggest draw of medicine is that it is scientific and analytic but has human interaction at its core. Looking back over the years, one of the things I am most proud of is winning an award for humanism in medicine when I was in medical school. I didn’t realise the significance of it at the time, but looking back on my career I hope that the traits that likely led to that recognition are what I am ultimately known for.

Interventional cardiology came later. I really liked the evidence-based medicine approach in cardiovascular disease combined with the fact that we could diagnose conditions and treat them therapeutically, but also with longitudinal care over time. Interventional cardiology isn’t just doing a procedure and never seeing the patient again—we manage patients both in and out of the hospital and even for years after their procedure. It’s the therapeutic aspects of the field—when someone has a problem that we can address with technical skill and also by using our brain—those are the parts of the field that most appeal to me.

Who have been the biggest influences on your early career?

My parents are both physicians and their kindness to others was a big influence on me. My mother taught me that in the long run it is best to be honest and fair, even if that leads to others hearing things they might not want to hear in the moment. She is under 5ft tall but never intimidated by anyone. My father is really cerebral but has always been the person that our relatives or friends call, no matter what medical condition they have. He always takes the call and provides whatever support they need. They are both athletes in their 80s.

Starting out in cardiovascular disease, Mike Gibson was my mentor. I met him in California and then subsequently we worked together for four years in Boston along with David Cohen and others. I have had the fortune to train and work in numerous places and I really appreciate the fact that I could learn from different people along the way. When I came to Columbia, Marty Leon, Jeff Moses, Roxana Mehran and Gregg Stone were all huge influences on me, along with so many others in our group. With anyone who is an influence the most important thing is to recognise that they are human beings. I’ve always looked to individual mentors for their specific strengths and tried to emulate and combine these with my own experiences and upbringing. We end up being the strongest we can possibly be because we are an amalgamation of the different attributes of all of the people, including our parents, that we have interacted with over time. But, it is also important to be unique. Trainees too often think they should emulate a specific mentor in every way and that can be too hard or disappointing. I try to take the good things that each has to offer and incorporate or emulate these in the best way that I can manage.

What has been the biggest technological advance during your career?

In my opinion it is the structural heart revolution. When I was a trainee, structural heart disease was basically just balloon mitral valvuloplasty for rheumatic mitral stenosis and the occasional aortic valvuloplasty. When I came to Columbia, transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) was in its infancy. Now we can treat all sorts of conditions that were either off limits to patients because they were too high risk for surgery or even offer a less invasive approach to those who previously only had surgery as an option. It is super impressive to see the results of the clinical studies as well as the techniques and the impact that they have had on our patients.

What has been the biggest disappointment?

I am an optimistic person by nature, so it is hard to get overly disappointed. Even a trial or a technology that has a negative result is a learning experience.

One area where I have been disillusioned more recently has been with the promise of social media to democratise medical education. While social media allows for rapid dissemination of information, so many of the negatives (for example, the loudest voices get the most play irrespective of merit) limit its ability to be a good educational tool.

But, I would also bet that of the people one might describe as being loudmouths or even trolls on social media, if you sat down and talked to many of them in real life, you might find them to be engaging and thoughtful people with valuable insights. In my estimation, the “social media world” is a very distorted version of the actual world, and that is why I’ve lost interest. I still hold out hope that there could be ways to use some version of it productively, but right now I don’t view social media as ‘social’ at all, I view it as paradoxically antisocial (except for the funny memes and jokes). I’m fairly certain that many agree with this sentiment, but for many there is too much fear of missing out to let it go, which of course is exactly the way it’s designed.

How do you see interventional cardiology evolving over the next decade?

I think some of the work that is being done in data science will spill over to the world of clinical trials. It could be argued that the randomised controlled trial was what really brought evidence-based medicine to the forefront of medicine. But one of the challenges that we have now is that even in a large randomised trial we get an average treatment effect across a large population of patients, but we know that in real life each of those patients are very different.

The next leap forward would be some application of personalisation within the context of a randomised trial, so that we don’t have to spend many millions of dollars for the ISCHEMIA trial, for example, to come out with an average treatment effect that we know a priori is nuanced when we try to apply it to our individual patients. I think it would be much better if we could really start to hone in on the patients that may or may not benefit from therapies in a much more intelligent way through the integration of personalised medicine with evidence-based medicine.

As an investigator of renal denervation for hypertension treatment, what impact do you see the recent US approval of two devices for this condition having?

I am excited by it. It has been a long road, and along that road I discovered how poorly treated hypertension is worldwide. To have a therapy that is independent of adherence and synergistic with medication and lifestyle modification is really important, especially for the highest risk patients.

I am an optimistic person, but also realistic, and I think what remains to be determined is how durable is the effect over the long-term. Is the responder rate what we think it is? If a third of patients are not going to get a response then that is going to be disappointing for them.

But I do think that this is a new paradigm in that it allows us to take care of patients in ways other than medication, and as physicians, too often in the office we prescribe medicine and assume patients are going to take it, but in real life patients don’t necessarily want to do that. So I am excited by it and I am certainly thankful to everyone who collaborated to bring this therapy forward.

What are your other current research interests?

Beyond getting renal denervation approved and furthering the study of its use, we just presented data that will hopefully lead to the first drug-coated balloon approval for use in the coronaries in the USA. On another front, we have completed the largest trial of adjunctive plaque modification for severe calcium—the ECLIPSE trial of orbital atherectomy—which we plan on presenting later this year.

I am very excited about the ALL-RISE trial that has just started, studying how angiography-based physiology with the CathWorks system compares to just wire-based physiology. I think everybody would agree that it is good to do physiology but it is often a pain to do and that is one of the reasons why it is underutilised. The idea of being able to get physiologic measurements using the coronary angiogram alone is appealing intuitively and we hope to show that the clinical outcomes will be similar or better compared to wire-based physiology, which I think could really change the way we look at diagnostic catheterisation going forward.

I feel that while a lot of our field’s attention has shifted to structural heart, the coronary space is still alive and well, and there is a lot we can still do to improve the care of patients with coronary artery disease.

Which recent studies have been particularly influential on your practice?

Sticking with the coronary theme, I would say the combination of the ISCHEMIA trial results and then the definitive sequel to the ORBITA trial, ORBITA-2, were pretty influential. Both tell stories that fit a picture, and that is that if you have either severe symptoms or severe disease, those are the types of patients that can benefit the most from what we would have to offer in the cath lab. We certainly have a lot to offer outside the cath lab with respect to medical therapy and prevention, but in the cath lab, the patients that benefit are those that are going to have the most severe symptoms or the most severe disease. Contrary to the popular (oversimplified) take on ISCHEMIA, there actually is a prognostic benefit to diagnosis and revascularisation of the most severe forms of coronary artery disease.

What is the most rewarding part of your job?

Every physician develops their own individual style—some would even call it a “brand”—and for me it is thoughtful clinical medicine. Medicine is at its heart based upon common sense, guided by knowledge and understanding. That means taking the data, understanding it well, understanding the nuances, trying your best to apply them to individual patients and their families within the context of their preferences and their upbringing, and having the technical ability and judgement to safely get them through a procedure if they need it. To me there is nothing better than that.

What keeps you occupied outside of medicine?

I have an amazing family. My wife has been a bedrock for me since we started dating at the age of 18. We have two grown-up kids and a dog and we love spending time together—I am really fortunate in that way. I am so thankful that while my kids are different from one another, both are truly wonderful—probably mostly due to the influences of my wife and extended family who have always surrounded us all with love. The four of us play music together, and that is a lot of fun. Now that the kids are out of the house, I find myself playing the guitar much more than I used to. Sports and exercise are always things that I have been interested in, and I love skiing in particular. I also have more time to read now too, especially given that I am off social media, and that is something I enjoy and have started to do more often.

Fact File

Current appointments

- Director, Columbia Interventional Cardiovascular Care program

- Professor of Medicine, Columbia University Irving Medical Center

- Chief Academic Officer, Division of Cardiology, Columbia Interventional Cardiovascular Care

- Program Director, Cardiovascular Research Foundation (CRF) Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics (TCT) conference

Education and Training

- AB in Molecular Biology, Princeton University

- MD, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons

- SM in Clinical Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Heath

- Internship, Residency and Chief Residency, University of California-San Francisco

Medical Center - Cardiology and Interventional Cardiology Fellowship, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center/Harvard Medical School