This advertorial is sponsored by Medtronic

Newly released joint guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) represent a major paradigm shift in the management of valvular heart disease. As well as bringing together the latest evidence and consensus on the treatment of mitral and tricuspid disease—reflecting a growing role for transcatheter therapies in these domains—new recommendations for the treatment of aortic stenosis establish an expanded role for transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) that will broaden the population of patients who are eligible for the therapy.

“The biggest highlight is the change in the age cut-off, which has moved from 75 to 70 years,” interventional cardiologist Vasileios Panoulas (Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals, London, UK) tells Cardiovascular News, reflecting on how the new guidelines will impact his practice. The updated guidelines underscore that for anatomically suitable patients aged 70 years or older who have a tricuspid aortic valve, irrespective of their estimated surgical risk, TAVI is a viable treatment option. “This opens the floodgate to a lot more patients who now have the opportunity for transcatheter therapy compared to surgery,” says Panoulas.

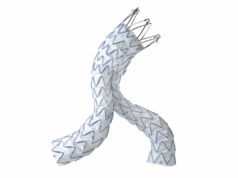

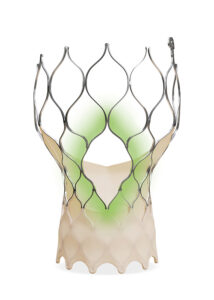

Treating patients with longer life expectancy brings long-term durability and haemodynamic performance into focus for heart teams when considering the best option for their patients. Long-term data from the NOTION trial have shown that, at 10 years, TAVI with Medtronic’s first-generation Corevalve platform held up to surgery for outcomes including all-cause mortality, stroke and myocardial infarction (MI), and demonstrated that TAVI patients had a lower risk of valve deterioration than those treated with surgery. Five-year data from the Evolut Low Risk trial, meanwhile, have demonstrated encouraging haemodynamics and low rates of valve dysfunction using the Evolut (Medtronic) valve. These data offer heart teams reassurance that TAVI is a long-lasting solution.

“As operators we need to strive to put in the valve that we think will last the patient as long as possible, because the ideal is not to have to put the second valve in at that stage. What valve will that be? It will be the valve with the longest survival data, it’s as simple as that,” says Panoulas.

Many factors contribute to the potential durability of the valve to function into the long term. Avoiding patient-prosthesis mismatch (PPM)—which occurs when the effective orifice area (EOA) of the implanted prosthetic valve is small compared with the patient’s body size—is recognised as one of the key components to ensuring longevity of the treatment amongst patients with a longer life expectancy.

This is highlighted in a recent paper from JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions, authored by Kazuki Suruga (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Smidt Heart Institute, Los Angeles, USA) et al, which demonstrated that amongst low-risk patients treated with TAVI with a balloon-expandable valve, the occurrence of PPM resulted in markedly worse clinical outcomes. In the single-centre study, Suruga and colleagues showed that patients with PPM had more than double the risk of all-cause death compared to those without, whilst the risk of cardiovascular death was nearly three-fold higher.

“There is a clear signal that we need to try and avoid patient PPM in this population, because clearly lower mismatch means longevity of the prosthesis,” says Panoulas of these findings. “It has been shown in the surgical literature that if you have severe PPM you fare worse in the long term, and there is no reason that is not the same for TAVI. Now we have the evidence to prove that.”

According to Panoulas, using a supra-annular valve design, like that of the Evolut series, is an effective way to minimise PPM. “Basically, you sit the valve higher than the annulus that might be small,” he comments. “As a rule, we have to strive to put in valves that have a bigger orifice area and less gradient. Regardless of what valve you are going to choose I think you need to make sure that has the best haemodynamic profile for your patients.”

Other considerations in patients with a longer life expectancy include the potential need for access to the coronary arteries in case of future coronary artery disease, a factor that may also have a bearing on valve choice. “When we talk about younger people, particularly if they might have coronary disease, you might have to think carefully what valve you are going to choose,”

adds Panoulas.

The latest-generation Evolut platform—Evolut FX+—offers three larger coronary access windows through a modified diamond-shaped cell designed, to provide increased space for catheter manoeuvrability to facilitate access to coronary arteries of varying patient anatomies, whilst also designed to maintain its structural strength and radial force.

According to Panoulas, this improvement is a big step forward in helping to facilitate coronary access. “With the big windows, coronary access is not a problem for the future. The latest iteration has really solved that big problem that used to be a deadly issue for the future.”

Minimising conduction disturbances to prevent pacemaker implantation are another potential consideration for the long-term needs of younger patients. Achieving commissural alignment, where the position of the implanted valve aligns with the native aortic commissures, is one factor to consider. Interventionalists can employ strategies such as the cusp overlap technique (COT) to assess and achieve the optimal implant depth to reduce interaction with the conduction system. In the Optimize PRO study, utilisation of COT with the Evolut PRO and PRO+ devices led to favourable procedural and clinical outcomes, with only a 6.4% rate of new 30-day permanent pacemaker implantation amongst patients whose valve was implanted in compliance with COT.

Later iterations of Evolut feature radiopaque markers—gold markers located close to the inflow edge of the valve and under the commissures that are visible on fluoroscopy to help operators align the valve with the native annular plane—with the intention of achieving commissural alignment to improve future access to the coronary arteries.

“You can align the commissures and make it easier for people, and I must say, having the experience with Evolut FX+ there is a very high chance of commissural alignment,” comments Panoulas.

Developing strategies to treat patients in the younger age bracket will also mean understanding the need to address aortic stenosis in bicuspid aortic valves. Patients with bicuspid aortic valves can see aortic stenosis at an earlier stage, as bicuspid valves tend to calcify and become stenotic earlier in life than tricuspid valves due to higher mechanical stress on the valves. Whilst the latest ESC/EACT guidelines suggest that surgery is the preferred option in bicuspid aortic valves, in line with data from the NOTION 2 trial which suggest operators exert caution in opting for TAVI in this patient subset, there will be so teams a suitable approach, for example in patients at increased surgical risk.

Analysis taken from a multicentre registry of patients with severe bicuspid aortic stenosis treated with Evolut, conducted by Gabriela Tirado Conte (Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain) et al and published in the European Heart Journal – Cardiovascular Imaging, using pre- and post-procedural cardiac computed tomography (CT), suggests that a “decoupling” between the inflow- and leaflet-level stent frame geometry of Evolut may provide an advantage in challenging bicuspid anatomies.

The study’s authors noted that fused bicuspid valve type (Sievers type 1) was associated with reduced inflow expansion compared to two-sinus type (Sievers type 0), while a calcified raphe resulted in greater inflow ellipticity, adding that these deformations at the inflow level had minimal impact on the Evolut stent frame geometry at the leaflet level, where circularity and expansion were preserved, and valve performance remained unaffected.

“These findings highlight the Evolut platform’s ability to maintain valve function despite anatomical challenges and offer valuable guidance for procedural planning in bicuspid aortic stenosis,” the authors write.

The new ESC/EACTS valvular heart disease guidelines mark an exciting new chapter in the evolution of TAVI for the treatment of aortic stenosis—but one that will require careful, evidence-based shared decision-making. A successful strategy will depend on valve choice that optimises durability, haemodynamics and lifetime management.